Recovering the role of women in Victorian politics has become a significant topic in our recent posts. Guest blogs by Sarah Richardson and Jennifer Davey and Martin Spychal’s series exploring the work of Harriet Grote, the wife of the Radical MP George Grote, have all shed new light on female participation in 19th century political life. Today’s guest post by Dr Jeremy Crump, one of our external contributors, continues this theme with a profile of Mary Pearson, wife of Charles Pearson, a Radical MP for Lambeth. Mary was an artist, whose skills were put to striking use within the political circles in which she moved.

Increasing attention is now paid to the role of mid-19th century MPs’ wives as leading figures in political salons, in campaigning at elections and in constituency work. But few achieved prominence in a professional capacity on their own behalf. For 25 years before her husband Charles became an MP for Lambeth in 1847, Mary Pearson pursued a career as a portrait painter, exhibiting at the major London galleries and winning commissions for painting portraits, including those of leading Liberals in the City of London. Paintings by Mary are now to be found in the National Portrait Gallery, the British Museum, the Guildhall Art Gallery and in the collections of London livery companies (a selection can be found on the Art UK site.)

Mary was born in the City of London in 1798. Her father, Robert Dutton, was a bookseller who kept a circulating library. According to an article in The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1826), she took to drawing early and was taught by a drawing master, Mr Lewis. She specialised in oil painting and from 1813 studied and copied old masters at the British Institution, at which she excelled. By 1815 Mary had begun to paint portraits and landscapes, winning medals for her views of the Rhine and Bodiam Castle, Sussex.

In 1815 Mary married Charles Pearson (1793-1862), a radical lawyer. His early success in campaigning against the government’s packing of juries in treason trials brought him to the attention of Henry Hunt MP, for whom he acted as solicitor at the time of the Peterloo Massacre. He was a member of the City of London’s Common Council from 1817-20 and again from 1830-6, when he became the chair of the city board of health and under-sheriff of London and Middlesex. After a period as a parliamentary agent he became the City’s solicitor in 1836, a position he held until his death. The couple had only one child, Mary Dutton Pearson, whom Mary educated whilst still finding ten hours a day to paint.

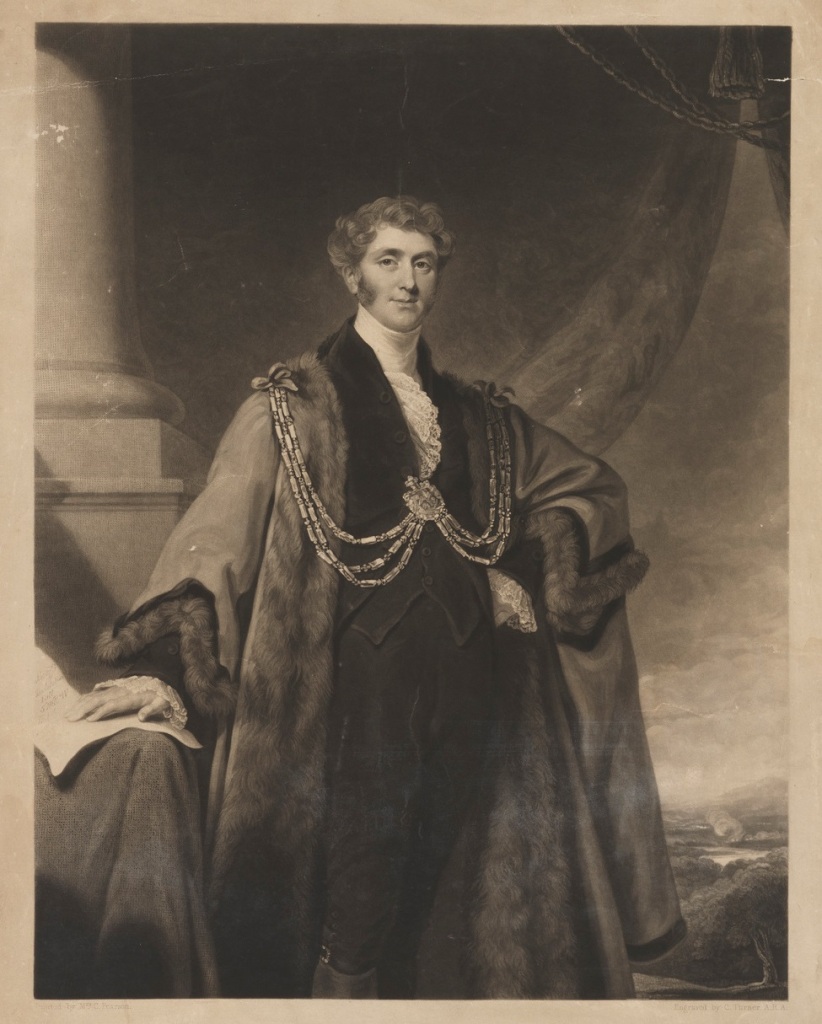

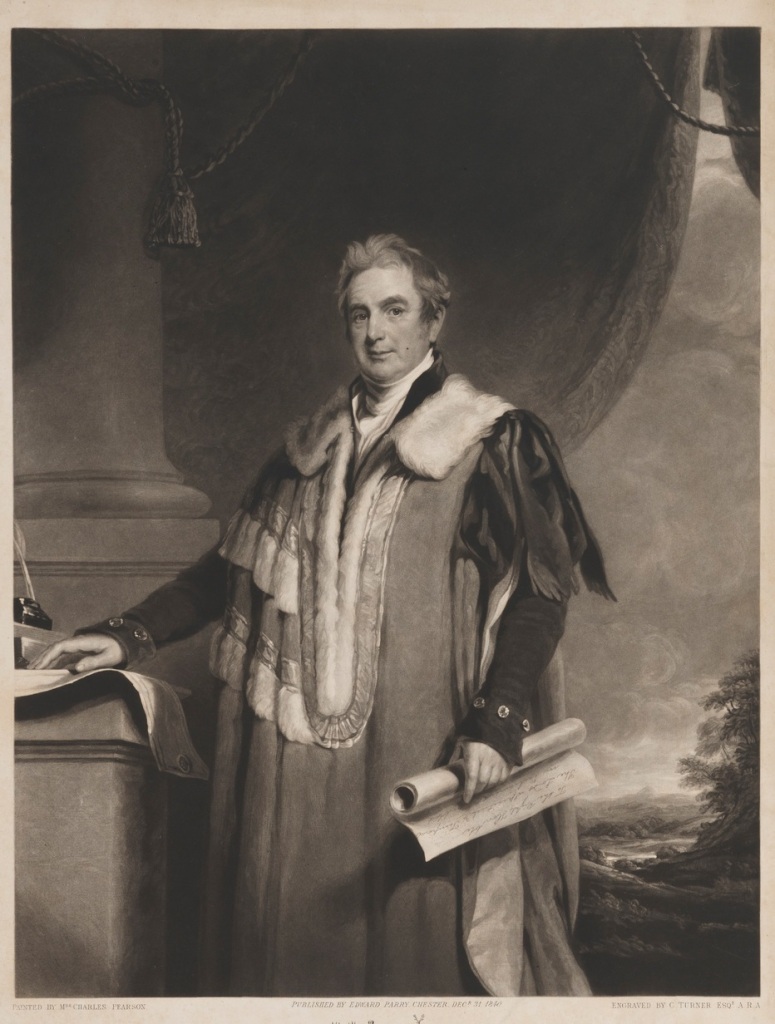

Between 1821 and 1842, Mary Pearson exhibited 31 portraits at the Royal Academy, 15 at the British Institution and 37 at the Society of British Artists. Her status as a painter of official portraits was established in 1825 when she painted Viscount Combermere, commander-in-chief of the army in Ireland. From 1831 onwards her publicly exhibited portraits were almost all of political subjects, predominantly City mayors and sheriffs, including Sir John Key and Sir John Pirie, the aldermen John Humphery (also a Southwark MP), David Salomons (MP for Greenwich from 1851), Henry Winchester (MP for Maidstone 1830-31) and the postal reformer, Rowland Hill. Her success coincided with Charles’s second period on the Common Council, where Key and Salomons were Charles’ political allies.

The Salomons portrait is characteristic of Mary’s grandest work. Salomons stands beside a Tuscan column in front of a rural background. His right hand is on a copy of the Sheriffs’ Declaration Act, which allowed sheriffs to take office without making the full religious declaration required by the 1835 Municipal Corporations Act. The measure was occasioned by Salomons’ election as Sheriff in 1835, and permitted him to become the first Jew to take up this office. Charles Pearson had been the leading advocate of a petition to give David Salomons the freedom of the City in 1831 and supported him for the office of Sheriff in 1835. Similar columns, draperies and backgrounds reappear in other portraits. Sir John Key is portrayed with a paper with the words ‘in favour of Parliamentary Reform Bill’ while Sir Edward Price Lloyd MP holds the scroll which bestowed on him the title of Baron Mostyn.

These formal portraits acknowledged political achievement. The Mostyn portrait, for instance, was a gift from ‘numerous Friends and admirers in testimony’ of ‘his long career of Public and Parliamentary usefulness’. Crucially, as Henry Miller has shown in his book Politics Personified, they also enabled the wider distribution of a politician’s image through reproductions as mezzotints, which were in turn reproduced in the popular press. A number of Mary’s portraits were made into mezzotints by Charles Turner, ‘Mezzotint Engraver in Ordinary to his Majesty’ and a friend and collaborator of J. M. W. Turner.

Mary was aware of her political role. In a letter to the Common Council in 1844, which accompanied her donation of a portrait of the leading Whig Thomas Denman, she remarked that she had been for many years allied to members of the Common Council, ‘by filial and conjugal ties’, and that her aim in the painting of Denman was

To convey to posterity an adequate resemblance of this distinguished individual, of whom it will be recorded in history, that when excluded by political considerations from the well-earned honours of his profession, he was elevated by the ancient privilege of the corporation of London to judicial station and forensic rank.

Denman had been a defender of Luddites and counsel to Queen Caroline and had been excluded from judicial office until his appointment as Common Serjeant by the corporation in 1822. This would be, she noted, her last major painting.

Writing about portraiture in the first decades of the 19th century in her English Female Artists (1876), the artist and writer Ellen C Clayton claimed that ‘never before nor since have so many English lady artists obtained such honours in a most difficult branch’. Nevertheless, the institutional environment in which Mary worked was restrictive. Even Margaret Sarah Carpenter, regarded by some contemporaries as a rightful successor to Sir Thomas Lawrence as the nation’s leading portraitist, was debarred as a woman from membership of the Royal Academy. During Mary’s career, the number of female artists exhibiting at the Royal Academy increased, but only marginally, from 32 out of 575 (5.6%) in 1821 to 52 out of 737 in 1842 (7.1%).

Mary Pearson’s retirement from public painting coincided with the marriage of her daughter to the timber merchant Thomas Gabriel, later Lord Mayor of London. Three years later in 1847 Charles Pearson became MP for Lambeth. His career in the Commons was a short one – the strain of combining this with his duties as the City’s solicitor prompted him to resign on grounds of overwork three years later. He put himself forward again in 1857 but, the day after his address appeared, he withdrew on the grounds that friends ‘in the Corporation and without’ had advised that, in view of his collapse in 1850, he should not seek to be a metropolitan MP while carrying out his role as solicitor to the Corporation. It seems likely that the friends included Mary Pearson. For the rest of his life Pearson campaigned for the creation of an underground railway system in London.

After Charles Pearson’s death in 1862, Mary Pearson lived with her daughter and son-in-law in Brighton. She died in 1871 and was buried in West Norwood cemetery, Lambeth. Her obituary in the Art Journal remembered her as ‘admired as much for her talent and winning sweetness of manner’. Her work was by then largely forgotten, but Ellen Clayton considered her to be ‘one of those really romantic heroines, who are hurriedly passed in this earnest, fast-fleeting era’.

JC

Further reading:

H. Miller, Politics Personified: Portraiture, Caricature and Visual Culture in Britain c. 1830-80 (Manchester, 2015)

Ellen C Clayton, English Female Artists (London, 1876)

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons