In the fifth of his blogs on Harriet Grote (1792-1878), our research fellow Dr Martin Spychal explores Harriet’s relationship with the veteran radical Francis Place (1771-1854), her views on radical tactics and her increasingly resourceful strategies for influencing Parliament during the 1835 and 1836 parliamentary sessions.

In September 1836 the veteran radical, Francis Place (1771-1854), shared his thoughts on one of his closest Westminster allies, Harriet Grote (1792-1878). While women could not vote or sit in Parliament (which would remain the case until 1918), he wrote that

she [Harriet], yes, she was the only member of Parliament with whom I had any [verbal] intercourse in the latter third of the [1836] session, we communicated freely, but we could find no heroes, no, no decent legislators.

Place’s suggestion that Harriet was a de facto MP was anything but a joke. As I’ve explored in previous blogs, during the 1830s Harriet enjoyed as much influence at Westminster as many of her male counterparts. This included her husband, the MP for London, George Grote (1794-1871). After George’s election in 1832, Harriet combined her role as a hostess, her growing correspondence networks, and a physical presence at Parliament to establish herself as one of Westminster’s leading politicians.

In early 1835 this culminated in an abortive attempt to mastermind the establishment of a radical party, capable of forming a government. As this blog discusses, over the following eighteen months, Harriet proved herself to be an accomplished political analyst and radical tactician. And with politics pushing her to her wits’ end by the summer of 1836, she put her words into action and sought out new means of influencing politics.

***

With the Whig government headed by Viscount Melbourne in place and her brief dreams of a radical administration scuppered, Harriet cut an increasingly cynical figure throughout 1835. This reflected a wider radical malaise with British politics, which had promised so much only three years earlier with the passage of the 1832 Reform Act.

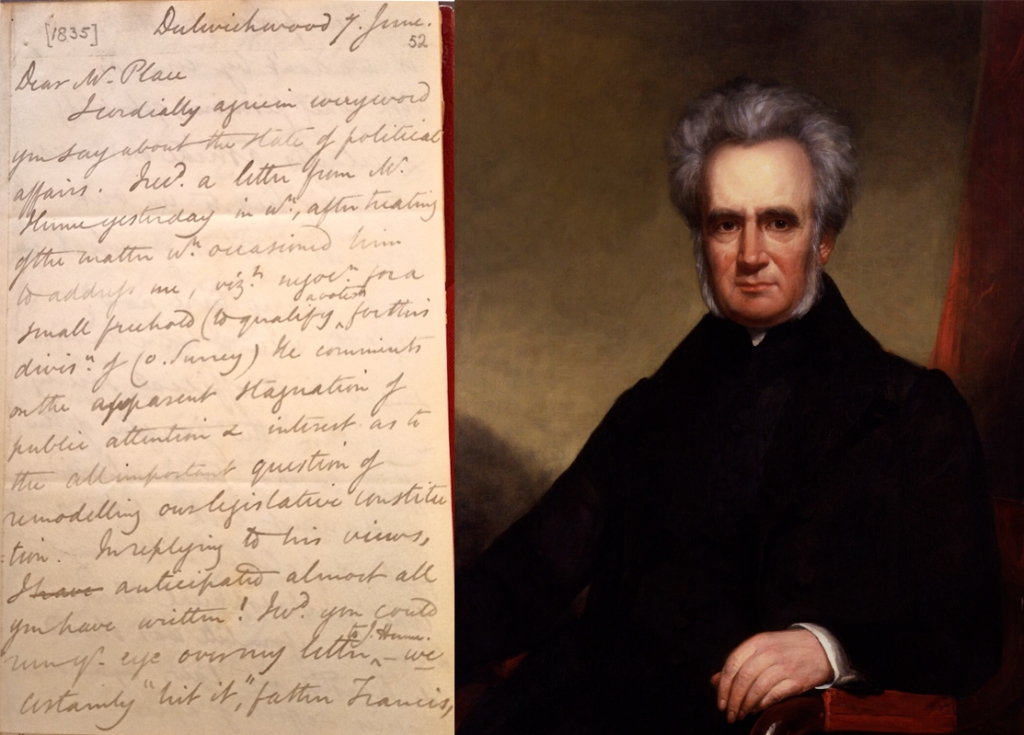

In June 1835 Harriet confessed her increasing frustration to Francis Place, regretting that ‘I have exerted myself as far as is becoming to my sex and position, to animate the good to courage’. The ‘good’ for Harriet were the pool of around 180 radical and reformer MPs returned at the 1835 election, who due to the lure of favours from the Whig government had become ‘timid’ in their politics. By contrast, Harriet felt that she and her dwindling band of allies had avoided such a fate by maintaining their independence: ‘we don’t by conversing with Whig pismires [ants], get Whig spectacles astride our noses, and Whig hearts in our breasts’.

For Harriet it was not just the lure of Whig patronage that had stalled radical progress. She perceived a deeper problem with the nation’s radical, male, leaders who were failing to fulfil their ‘duty’ as ‘popular organs’ in Parliament. ‘If popular representation be good for anything’, she wrote to Place, ‘it is because the “organs” are sent up there to lead and to give the tone to the public mind’. In fact, reformer and radical MPs were doing nothing of the sort. She continued:

If after all the sweating, the striving, the bawling and the paying to get your man seated, he is to do nothing, but sit there waiting for the people to agitate and consult and direct him what to do! Stuff, besotted ignorance, swinish ignorance. If I ain’t sick and tired of seeing the whole rationale of representation virtually repudiated and nullified by the twaddle men in and out of Parliament (but chiefly by men in P[arliament] to this disgrace be it spoken).

Harriet’s assessment of parliamentary radicalism continued to worsen over the following year. This was compounded by a period of illness that kept her away from Westminster during the first months of the 1836 parliamentary session. When she returned to London in May 1836 she was dismayed with the continued disorganisation of radical forces. She advised one correspondent: ‘I have been in town for a day or two and observe with regret that our party does not appear braced for vigorous action’.

Her brief absence had confirmed her belief that her constant presence was required at Westminster to prevent George, and the entire radical parliamentary cause, from falling foul of Whig advances. She advised Place:

My motive for going up [to London] is the grave importance of this juncture. [George] Grote likes of course to have me at hand when any emergency falls out likely to draw him forth. I carried him up to the best of my power last year [1835], and with effect against the vehement railing of Joseph Parkes, who wanted to muzzle him about the English Municipal Reform Bill!

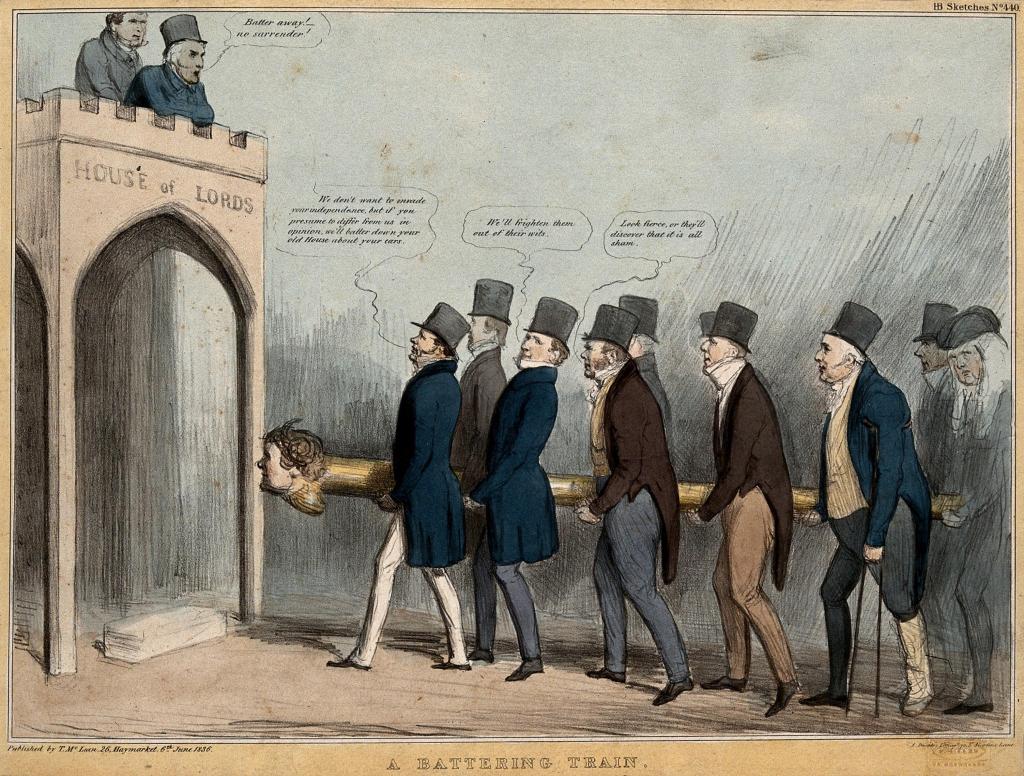

The important ‘juncture’ was the opportunity that political circumstances had presented for establishing House of Lords reform, or ‘peerage reform’ as it was also known, on the political agenda. The issue had recently been given publicity by the leader of the Irish Repealers, Daniel O’Connell, who had announced his intention for a parliamentary motion on the issue. However, Harriet dismissed O’Connell’s motion as futile gesture politics. Here was another radical parliamentary motion (in a crowded agenda of radical parliamentary motions) that was certain to fail.

Instead, Harriet wanted to use the House of Lords’ recent amendments to the government’s Irish municipal reform proposals to begin a long-term campaign of exposing the power of the unelected peers. She advised Place:

Here is a plain quarrel [Irish municipal reform], on a broad and definable ground, the real rights of England and Ireland. There is no “jug” in it, no sectarism. There is no “vested rights” in the way, there is no sacrifice of money to compensate injured parties. There never can be a more favourable position for the popular men to improve into strength, and the people see clearly now, that legislation unfairly stopped by the Ho[use] of Lords.

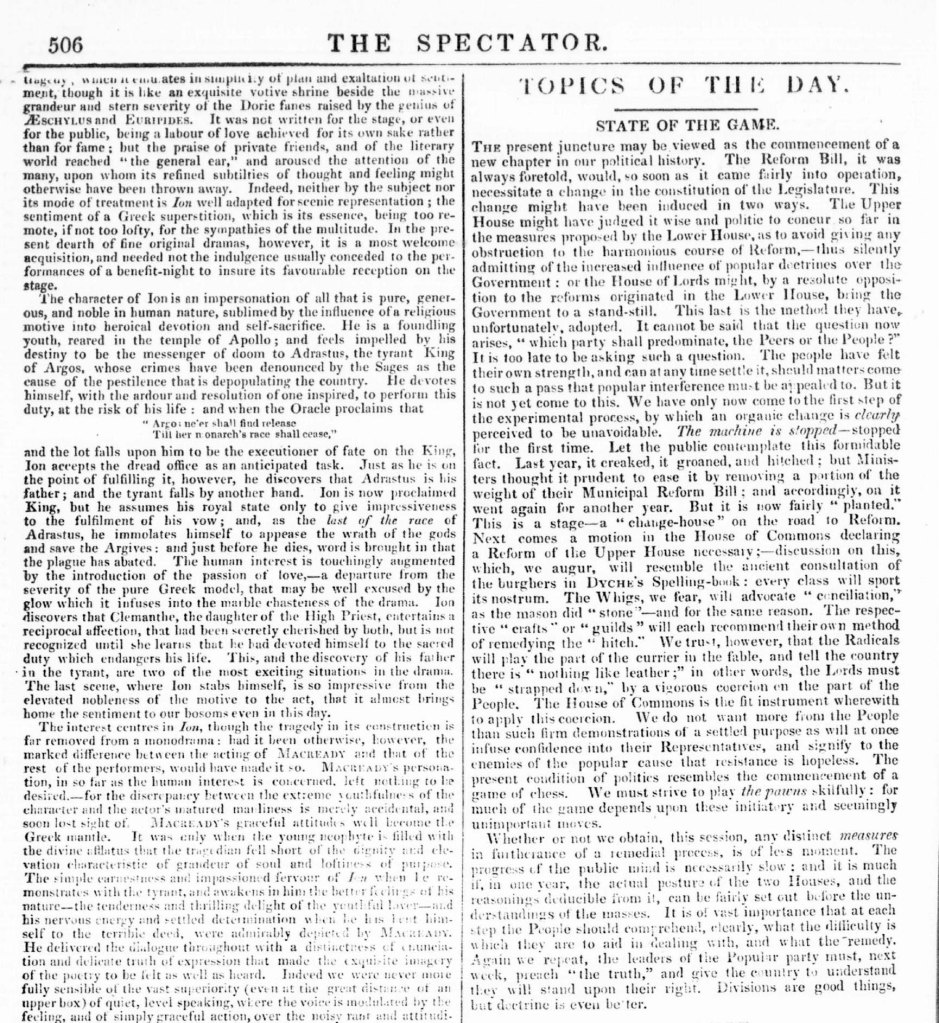

As George and his colleagues were doing little to set the political agenda, Harriet took matters into her own hands. She called in a favour from one of her closest contacts on Fleet Street, the editor of the Spectator, Robert Rintoul (1787-1858). Harriet couldn’t sit in Parliament, or speak on the hustings, but she could publish anonymously in the press.

In an article in the 28 May edition of the Spectator Harriet urged the leaders of the ‘popular party’ to ‘preach the truth’ on the necessity for peerage reform. She also demanded ‘vigorous coercion on the part of the people’ to ‘signify to the enemies of the popular cause that resistance is hopeless’. She was under no illusions as to the speed at which reform could be expected: ‘the present condition of politics resembles the commencement of a game of chess. We must strive to play the pawns skilfully’.

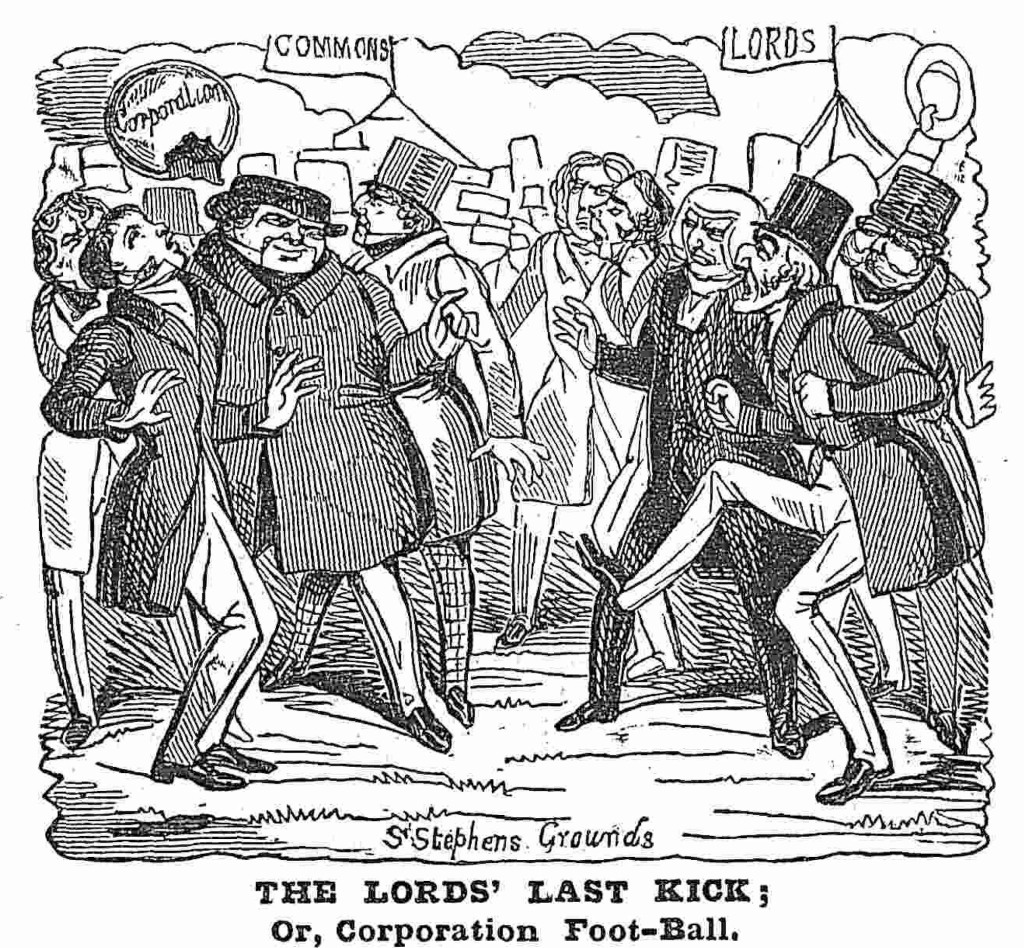

As well as setting the tone for a long-term campaign, Harriet began to orchestrate parliamentary tactics. The Lords’ amendments to the Irish municipal corporations bill were about to return to the Commons. And rumour in Westminster suggested that the Whig government would agree to some form of compromise. Radicals and reformers could not compromise, so she began to organise a motion rejecting the Lords’ amendments. She told one correspondent:

I have used all the influence I possess, without I trust stepping out of my province, to hearten up our lads to take a division upon a stout motion for sending back our bill, intact, to the Lords. Nous venons! [we come!]

For Harriet, the strategy provided the ‘few Roman souls’ in Parliament with the opportunity to distance themselves completely from any ‘shuffling dirty compromise on the part of the Whigs’. She advised another friend, ‘if the Whigs attempt to drag the Radicals in the mud anew, all I can say is the Rads ought to turn restive’.

Within days of her Spectator article and attempts to corral a radical rebellion, the Whig government backed down and refused to accept the Lords’ amendments. The bill did not pass that session, and the continued intransigence of the Lords meant that Irish corporation reform would not pass for a further four years. For a few years, at least, this helped to keep peerage reform at the top of the radical agenda.

For Harriet the episode served another important purpose. It confirmed the necessity of her constant presence at Westminster. By the end of the 1836 parliamentary session, she and George had sold their Dulwich Wood residence and purchased a central London house in Belgravia, at 3 Eccleston Street. After a brief trip to Paris that autumn, Harriet was ready to resume full political activity…

To read part six of Martin’s blog series click here

Further Reading

S. Richardson, ‘A Regular Politician in Breeches: The Life and Work of Harriet Lewin Grote’, in K. Demetrious (ed.), Brill’s Companion to George Grote and the Classical Tradition (2014)

J. Hamburger, ‘Grote [née Lewin], Harriet (1792-1878)’, Oxf. DNB, www.oxforddnb.com

W. Thomas, ‘Place, Francis (1771–1854)’, www.oxforddnb.com

Lady Eastlake, Mrs Grote: A Sketch (1880)

H. Grote, Collected Papers: In Prose and Verse 1842-1862 (1862)

H. Grote (ed.), Posthumous Papers: Comprising Selections from Familiar Correspondence (1874)

M. L. Clarke, George Grote: A Biography (1962)

Pingback: ‘Another of my female politicians’ epistles’: Harriet Grote (1792-1878), the 1835 Parliament and the failed attempt to establish a radical party | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 – The History of Parliament

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Mary Martha Pearson (1798-1871), political portraitist | The Victorian Commons