In this week’s blog our senior research fellow, Dr Martin Spychal, discusses the ‘whipping’ activities of the Conservative MP for Bridgnorth, Henry Whitmore (1813-76). Despite the disdain for his competence among the party leadership, he acted as Conservative deputy whip for much of the 1850s and 1860s.

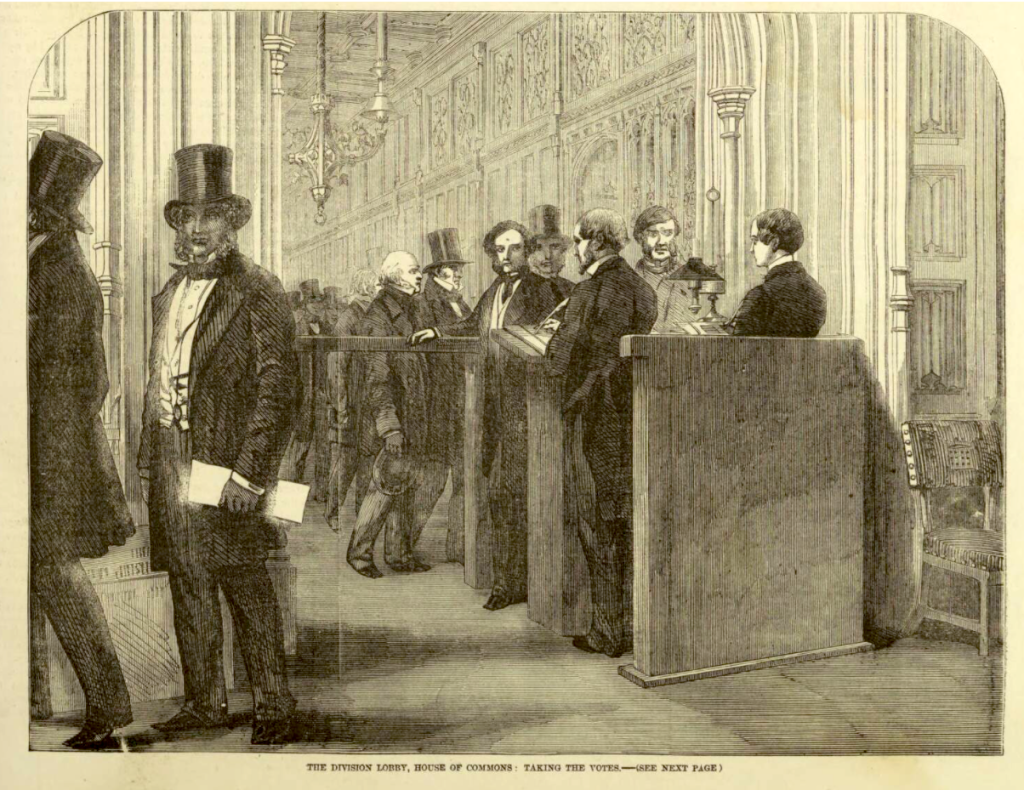

Party whips played an increasingly important role at Westminster following the 1832 Reform Act. In a new era of ‘parliamentary government’, the need to organise MPs’ behaviour became essential to both the Whig-Liberal and Conservative leaderships. Through their prototypical chief and deputy whips, both parties developed elaborate correspondence systems to ensure MPs’ attendance at Westminster. They were also increasingly systematic in using ‘party’ tellers in parliamentary divisions – a practice that was aided by the creation of a second division lobby in 1836. As well as organising party activity at Westminster, party whips also assumed responsibility for election management and party patronage.

The job of the party whip was complicated by the still fluid (and often fractured) nature of party at Westminster between 1832 and 1868. MPs were not ‘members’ of a parliamentary party in a modern sense. Furthermore, independence from party remained an important aspect of MP identity. That said, for a government, or an opposition, to function effectively, organisation was required. And it was down to the chief whip and his deputies to corral parliamentary colleagues, no matter how unwilling MPs were to operate collectively.

One mainstay of the Conservative whipping operation of the 1850s and 1860s was the MP for Bridgnorth, Henry Whitmore. His ancestors had represented the Shropshire constituency since the seventeenth century, including his father, Thomas (1782-1846) and brother, Thomas Charlton (1807-65).

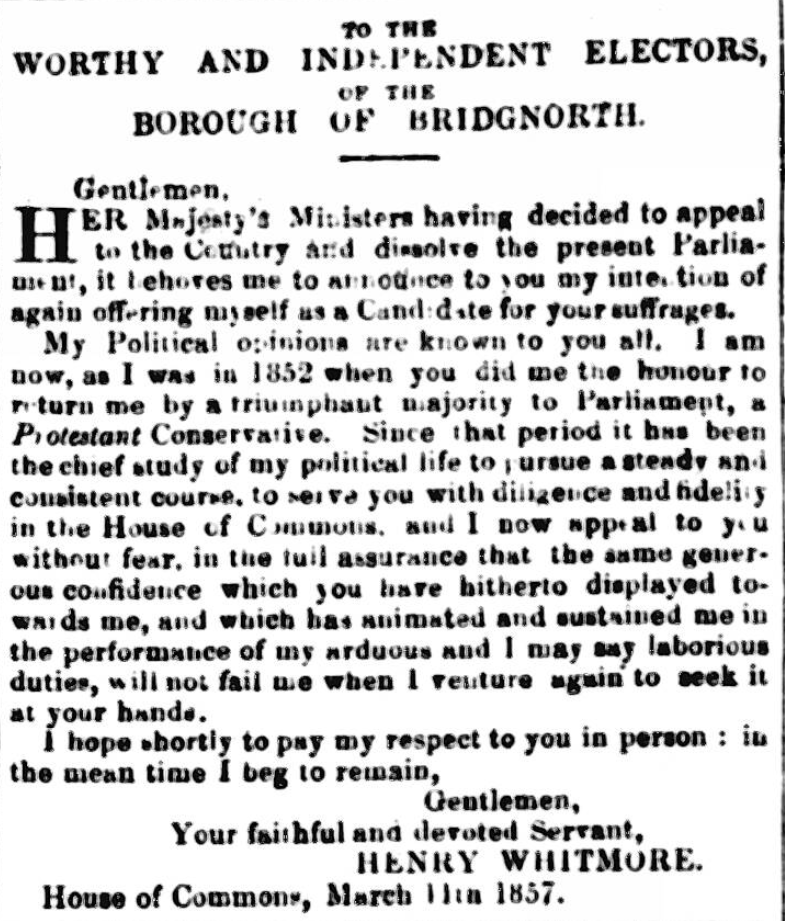

Whitmore replaced his brother as MP for Bridgnorth in 1852. Sitting on the right wing of the mid-Victorian Conservative party, in public he described himself as a ‘Protestant Conservative’. Viewing the Commons as a primarily ‘Christian assembly’, he opposed the admission of Jews to Parliament and voted against constitutional concessions to Catholics. As a whip, the stridency of Whitmore’s views proved a source of tension with the more moderate Conservative leadership of Lord Derby and Benjamin Disraeli. However, both Derby and Disraeli also understood Whitmore’s alliances with the right of the party as a potential asset in convincing recalcitrant MPs to unite under a Conservative banner.

In August 1855 Whitmore formally assumed the position of ‘third whip’ for the Conservative opposition, justifying his decision to sacrifice his independence on the basis that a disciplined opposition at Westminster was ‘absolutely necessary for carrying on the affairs of a nation’.

Whitmore was subsequently appointed a junior lord of the treasury (the formal job title associated with a deputy whip) in the Conservative Derby government of 1858-9. He attended 90% of recorded votes during the government, when he appears to have been a constant presence at Westminster.

At the 1859 election he claimed to be ‘a willing slave’ to the Conservative leadership, stating that his work for the party was a ‘labour of love’. The language he used to describe his official responsibilities was mocked on the hustings, particularly when he claimed that acting as a whip qualified him as ‘working class’ on the basis that the role required him to be ‘up in the morning labouring hard at work’.

When the Conservatives entered opposition later that year, the retirement of the previous chief whip meant that Whitmore was elevated to second whip. In private, the new chief whip, Thomas Edward Taylor, advised Disraeli that Whitmore was not suitable for further promotion. As a result Disraeli restricted Whitmore to a predominantly secretarial role, recording that the latter was ‘in the habit of assisting me in my correspondence from the Ho[use] of Commons’. Following this, Whitmore’s attendance of recorded votes in the Commons declined from 90% to 30%.

When he was called to whip votes, he became increasingly obstinate. On one occasion he was reluctantly roped into a cross-party whipping operation to aid Palmerston against an ‘embarrassing radical motion’. In April 1863, a ‘much out of sorts’ Whitmore obeyed orders for a ‘strong whip’ of Conservatives over a proposed minor electoral reform. He then personally abstained from the vote on the basis that it would ‘be injurious’ to his electoral interests at Bridgnorth.

On the appointment of the Conservative administration in July 1866, Disraeli advised the prime minister Derby that the latter was obliged by convention to re-appoint Whitmore as a government whip. Disraeli advised Derby that:

the case of a whip is not like that of a follower, who formerly, for a brief space, held parliamentary office. It is continuous service. Here are 14 years of continuous service – & if not very effective, at least honorable, loyal, & sincere. We put him [Whitmore] in the place, or at least our representative, [William] Jolliffe, did, & we are bound to guard him from unnecessary mortification.

Disraeli confirmed that the chief whip, Taylor, was still ‘prejudiced against’ Whitmore and looked looked forward to proposed reforms to the Treasury that would ‘require his resignation, & the presence of a lord [of the treasury] of financial aptitude & attainments’.

Much to Whitmore’s dismay, Taylor also secured the appointment of the MP for Rutland, Gerard Noel, as a joint second whip. Despite Noel’s lack of experience, Taylor groomed him to be his successor. This initiated an unconventional practice where Noel and Whitmore alternated as government tellers during the 1867 and 1868 sessions. As the 1868 session dragged on, an increasingly alienated Whitmore was rumoured to be under consideration for a colonial governorship in Tasmania, a proposal that was probably mooted by Disraeli to remove Whitmore from the whips’ office.

Whitmore remained at Westminster but was further ‘disheartened’ following the 1868 election when he received the news that Noel was going to be appointed chief whip. He complained to Disraeli:

after a term of 16 years to my party, during 13 of which I have acted as ‘whip’, I am suddenly superseded by the promotion of a junior [Noel] to the post to which I had so long naturally aspired, and which I was led to believe would have been offered me.

Whitmore informed Disraeli that ‘it would be impossible’ to continue as deputy whip unless the government compensated him for his embarrassment by granting him a baronetcy. Disraeli, now back in opposition, refused to be blackmailed and waited for Whitmore to resign. In December 1869 Disraeli got his way. In his letter of resignation Whitmore stated:

the appointment over my head of Noel my junior in office . . . was so keenly felt by me as a marked slight: and an act of injustice that I lost heart in my work and ceased to have any confidence in those whom I had trusted but by whom I had been betrayed.

Whitmore accepted the Chiltern Hundreds in February 1870, retiring from Parliament. He died six years later at his London residence. For those interested in finding out more about Whitmore, his correspondence with his first chief whip, Sir William Jolliffe, is held by Somerset Heritage Centre.

MS

Further Reading:

J. Sainty & G. Cox, ‘The Identification of Government Whips in the House of Commons 1830–1905’, Parliamentary History (1997), 339-58

T. A. Jenkins, ‘The Whips in the Early-Victorian House of Commons’, Parliamentary History (2000), 259-86

Angus Hawkins, ‘Parliamentary Government’ and Victorian Political Parties, c. 1830–c1880′, EHR (1989), 638-69

P. Salmon, ‘Politics beyond party: the survival of non-partisan traditions, 1832-68’, Victorian Commons (2023)