Our recent History of Parliament / University of East Anglia conference on ‘Politics before Democracy’ featured over 30 papers on topics ranging across the 18th and 19th centuries. Over the next few weeks we’ll be posting some summaries as part of a guest blog series. To start us off, Professor Sarah Richardson explores how widows, many of whom could vote in local elections, assumed a central place in some of the earlier debates about giving women the parliamentary vote.

According to the Earl of Salisbury in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part III, among the heinous crimes that should not be pardoned, even if enacted under solemn oath, were rape, murder, robbery and wringing ‘the widow from her customed right’. The widow’s ‘customed right’ was of course her property or dower, and with property ownership came the right to vote, or did it? Women’s suffrage campaigners in the 19th century argued bitterly that parliamentary and ‘judge-made’ laws had indeed deprived widows of their long-held right to the franchise. Although the same arguments applied to single women, the widow franchise was emphasised, partly because of the numbers – a substantial majority of women enfranchised by their property ownership would be widows – and partly because, in the eyes of many commentators, widows had fulfilled the designated function of women by marrying and possibly bearing children.

The 1832 Reform Act removed any doubt that women property owners could vote in parliamentary elections, vesting the franchise in ‘male persons’. When Mary Smith, a widow, petitioned the Commons against the reform, she framed her objections by stating that she paid taxes and therefore did not see why she should not have a share in the election of a representative. In addition, she stated that as women were liable to all the punishments of the law, they ought to have a voice in the making of it. Her voice went unheeded and the petition, like many that followed, was ignored.

Women could, however, vote in parish polls. My analysis of the polls for the election of an assistant overseer of the poor in Lichfield in 1843 and for the municipal corporation of Basingstoke in 1869 demonstrates that around 75% of women voters were widows, with the remainder unmarried. Women voters tended to be older – the average age for Basingstoke voters was 57 – but they ranged across the socio-economic spectrum. In Lichfield, the wealthiest woman voter was Grace Brown, a butcher who had been widowed and probably taken over her husband’s business. But the electorate also included Caroline Edge, a 35 year old washerwoman and widow with 6 children aged between 5 and 15.

In the 1860s the debate about the ‘widow franchise’ was reignited by the efforts of John Stuart Mill and Jacob Bright to remove the ‘disability’ preventing women property owners becoming voters.

MPs opposing women’s enfranchisement viewed extending the vote to widows and spinsters as ‘the thin end of the wedge’, words repeated in almost every debate from 1867 onwards. For example, the Conservative John Karslake challenged Mill’s amendment stating that:

spinsters and widows … were in a transition state—the spinsters might marry, and the widows might marry again. Now, if the ladies of England were once to obtain this boon—this inestimable boon of the franchise could the House expect that they would part with it again by marrying? … if the hon. Member got in the thin end of the wedge by the admission of unmarried women to the electoral roll he would afterwards claim that married women should also be admitted to the franchise.

Edward Pleydell-Bouverie argued that Jacob Bright’s 1872 bill would enfranchise only ‘the failures’ of the sex. Bright angrily responded:

if it be true that widows, the mothers of families whose husbands are dead, are the failures of their sex—then I admit my Bill enfranchises failures. In bringing in this Bill I am standing on the ancient lines of the Constitution; I am asking that those who have the local vote should have the Parliamentary vote also.

MPs simultaneously cast widows as poor, desperate women who would be subject to undue influence, or as strong survivors whose households should be represented. The Liberal MP Sir Maurice Levy, in a debate on the conciliation bill in 1911, asserted:

Such of the poorer classes as would be enfranchised by this Bill are, in the main, widows—probably old, we will trust mostly old … these women are largely in the power of the propertied people in this country, and consequently you will be placing on the register a very dangerous element of electors.

In contrast, the Labour MPs David Shackleton and Keir Hardie drew attention to the resilience of working-class widows. Hardie estimated that in his constituency 2,000 of the 2,600 women who would get the vote were working women, widows for the most part whose husbands had been killed at their work or had died comparatively young. And Shackleton noted:

Many a poor widow left with children has to face the battle of life and provide shelter and food for her family. In her efforts she joins in the responsible work of the State and of her district, and yet she is debarred from exercising the vote.

Early women’s suffrage societies had limited their objectives to giving widows and single women who were heads of households the vote, so that it would be on the same terms as male voters (4 in 10 of whom did not have the vote after 1885). They focused on practical measures and in the 1860s major challenges came from three intrepid widows from Manchester.

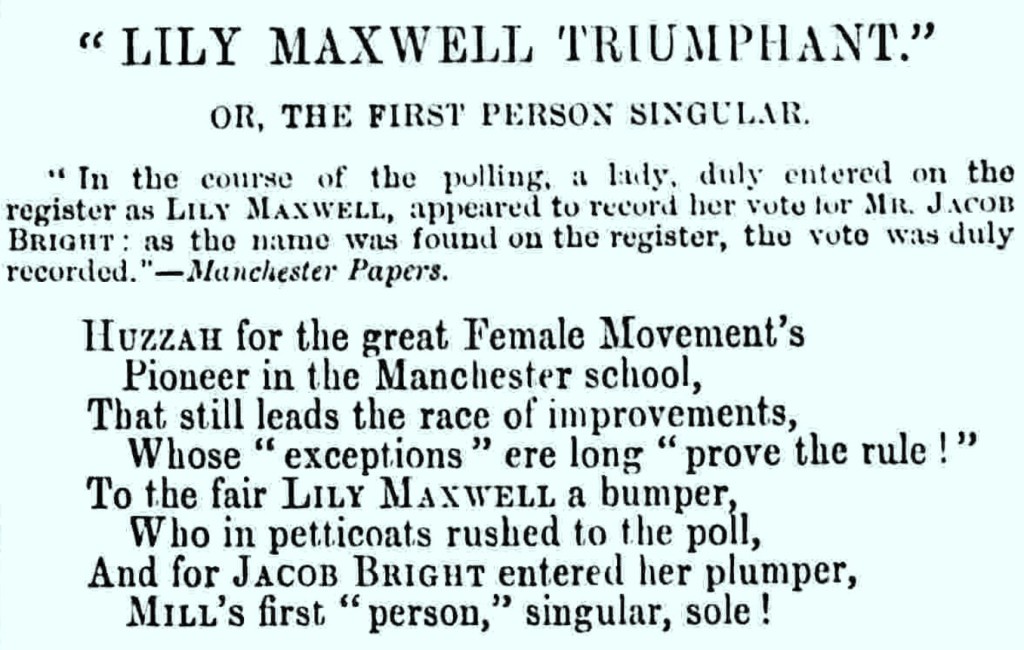

On 26 November 1867 a woman, Lily Maxwell, cast her vote in a by-election at Manchester, for the pro-women’s suffrage candidate, Jacob Bright. Maxwell was a widowed, rate-paying, head of household and a member of the shop-keeping middle-class as opposed to being a member of the elite, therefore Bright could present her as:

a hardworking, honest person, who pays her rates as you do; who contributes to the burdens of the State as you do; and therefore, if any woman should possess a vote, it is precisely such a one as she.

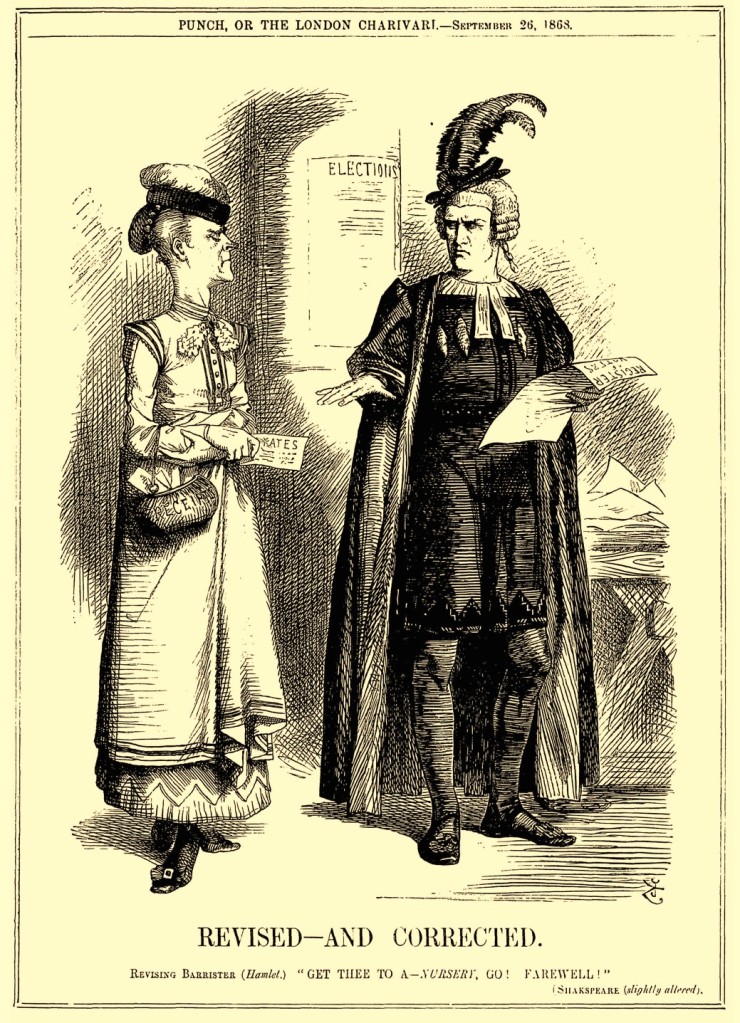

Following Maxwell’s vote, women across the country, including over 5,000 in Manchester alone, who had the necessary property qualifications, forwarded their names to local overseers of the poor to be entered on the voting lists. By September 1868, their cases were coming before the revision courts which finalised the electoral registers and the confused barristers overseeing the objections took contradictory decisions.

On 7 November 1868, the right of widows to vote in parliamentary elections was tested in the Court of Common Pleas in the cases Chorlton v. Lings and Chorlton v. Kessler. The cases centred on the inclusion of two Mancunian widows whose names were on the register: Mary Abbot and Philippine Kyllman. Rejecting the case, the Chief Justice found that as Parliament had not expressly stated that women could vote, they should be excluded.

The furious debates about the widow franchise in the 19th century were important because they illuminated the contradictions in the reformed electoral system between the key principle of property ownership and that of the sex of the owner. Inadvertently, they also moved the debate about the franchise forward, away from a focus on property and the representation of interests and towards one where the vote was vested in the individual, be that person male or female, unmarried, married or widowed. And formidable widows were pivotal in helping to achieve this sea-change in public and parliamentary opinion.

SR

Further reading:

Sarah Richardson, The Political Worlds of Women: Gender and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Britain (2015)

Catherine Hall, Keith McClelland and Jane Rendall, Defining the Victorian Nation: Class, Race, Gender and the Reform Act of 1867 (2014)

P. Salmon, Electoral Reform at Work: Local Politics and National Parties, 1832-1841 (2011)

Pingback: Mary Martha Pearson (1798-1871), political portraitist | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Marrying for the vote: the freedom-by-marriage franchise before 1832 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons