In the third of his blogs on Harriet Grote (1792-1878), our research fellow Dr Martin Spychal looks at Harriet’s introduction to politics at Westminster during the first ‘reformed’ Parliament of 1833-34.

Harriet Grote (1792-1878) was one of the most important British politicians of the 1830s. As I’ve discussed in my previous blogs, she had been a key figure among London’s intellectual radicals during the previous decade, before embracing national politics, alongside her husband, George Grote (1794-1871), during the reform crisis of 1830-32.

In the aftermath of George’s election as MP for London in 1832, Harriet wasted little time establishing herself at Westminster. At a time when women weren’t allowed to vote or sit in Parliament (or for that matter play any formal, public role in political life), Harriet became a highly influential figure behind the scenes at Westminster. One of the first things that she did was to establish herself as the hostess of 34 Parliament Street, which quickly became a political hub for reformers and radicals during the 1833 parliamentary session.

The 1832 election (the first election after the 1832 Reform Act) returned one of the most radical Houses of Commons in UK history. When Parliament convened in January 1833 around a third of Westminster’s 658 MPs described themselves as either Reformers, Radicals or Repealers, as distinct from the governing Whigs or opposition Conservatives.

One of the key political issues that served to unite these radicals and reformers (or the ‘popular party’ as Harriet described them) was their demand for additional electoral reforms beyond those granted by the 1832 Reform Act. Top on their list was the introduction of secret voting or ‘the ballot’, which it was hoped would put an end to illegitimate aristocratic and landlord influence at elections.

In January 1833 Harriet and George hosted discussions among Parliament’s reformers and radicals (including veteran radical MPs Henry Warburton and Joseph Hume) to identify who would spearhead the issue in Parliament. With Harriet ‘joining most cordially in the counsel’ it was agreed that her husband George ‘should be the person to undertake the ballot question in the ensuing session of Parliament’.

As I will discuss in a future blog, Harriet was one of the chief organisers of the popular, though ultimately futile, national campaign for the ballot during the 1830s. In the immediate context of 1833, however, it provided her with an opportunity to announce herself to Parliament and to extend her network of political contacts.

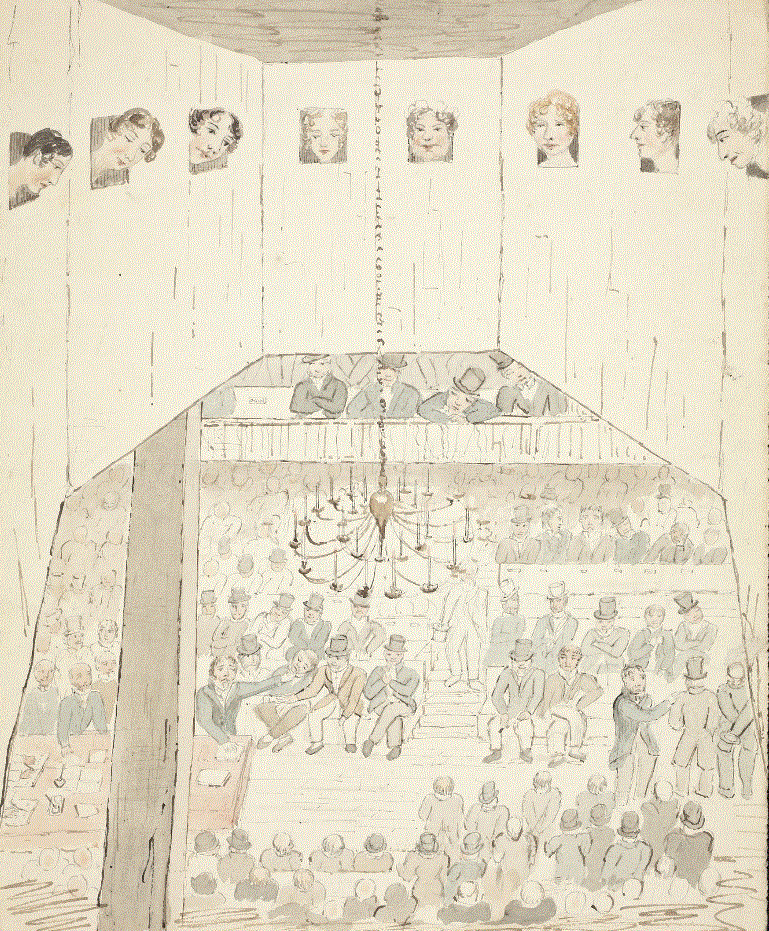

One of the most important physical sites of women’s engagement in the House of Parliament prior to the fire of 1834 was an informal women’s viewing gallery above the Commons, often referred to as the ‘ventilator’. Harriet preferred to call it ‘The Lantern’, observing that it allowed for ‘ten or twelve persons’ to be ‘so placed as to hear, and to a certain extent see, what passed in the body of the House’.

In preparation for George’s impending parliamentary motion on the ballot, in February 1833 Harriet ‘made an experiment’ and attended the ventilator for the first time. ‘Going with Fanny [Frances] Ord’, the wife of the MP for Newport, William Henry Ord, Harriet reported that ‘one hears very well, but seeing is difficult, being distant from the members, and the apertures in the ventilator being small and grated’.

When the night eventually arrived for George to introduce his first ballot motion, Harriet effectively held court in the ventilator before hosting a soiree at their Parliament Street residence.

After listening intently to George’s hour-long speech, she described how ‘immediately afterwards’ William Molesworth (MP for East Cornwall) ‘joined me upstairs, in the roof of the House’ and ‘poured out his admiration of [George] Grote’s performance’. In what soon became an annual tradition (on account of George’s repeated parliamentary motions for the ballot), ‘the whole corps of Radicals’ then descended on 34 Parliament Street ‘to come and pour out their congratulations’ for their efforts in promoting the cause.

The Grotes’ association with the ballot instantly elevated them to the forefront of British radical politics. This position was cemented over the following year by Harriet’s unceasing efforts to forge alliances with those she identified as the most important ‘respectable Rads’ at Westminster and beyond.

Harriet quickly cultivated an inner circle of leading politicians, thinkers, journalists and lawyers, who she invited to extended weekend political salons at the Grotes’ ‘country residence’ in Dulwich Wood. As well as the aforementioned Henry Warburton and Joseph Hume, senior radical dignitaries such as Francis Place might be found there on a Saturday evening talking political strategy with Harriet and George in the company of rising new MPs such as John Arthur Roebuck, Charles Buller and William Molesworth, the editor of the Spectator, Robert Rintoul, the writer Sarah Austin, or the young utilitarian, John Stuart Mill.

She was even willing to defy social convention and drive her guests back into London after their stays, offering another opportunity to extend her political influence. In one particularly revealing passage, in 1834 Harriet recalled:

driving my phaeton to London one morning [from Dulwich Wood], with Molesworth by my side, C[harles] Buller and Roebuck in the seat behind. During the whole six miles, these three vied with each other as to who should make the most outrageous Radical motions in the House [of Commons], the two behind standing up and talking, sans intermission, all the way, to Molesworth and myself.

Unfortunately for Harriet her efforts to organise Westminster’s reformers and radicals did not translate into immediate political results. Parliament itself, she lamented, still contained a majority of ‘men so lamentably deficient in patriotism and purity of principle’ that substantive change did not appear immediately likely. These ‘deficient’ men included the Whigs and the Conservatives, who had effectively formed an alliance of the centre to frustrate radical policy, and the ‘coarse and violent’ (in Harriet’s words) leader of the Irish Repealers, Daniel O’Connell, whom she never trusted.

Harriet’s hope that the Whig government of the 2nd Earl Grey might support her radical ambitions was quashed within a single Parliament. It was for this reason that she relished one small political victory in June 1834, when her husband, together with Henry Ward, MP for St. Albans, introduced a crucial vote over the funding of the Irish Church. The vote prompted the resignation of two cabinet ministers. A month later the Grey ministry would resign.

The ‘rupture of the Cabinet on the Irish Church question, has put us in great spirits’, Harriet informed her sister. What made this moment so positive for Harriet was that in voting against the Whig government, previously subservient MPs appeared to be acting on behalf of the people, rather than aristocratic, ministerial self-interest. The vote ‘was a remarkable proof’, Harriet wrote, of

how powerful the popular party are in that House, for the men who usually support this Government were forced from fear of their constituents to abandon the Ministers.

In my next blog I’ll turn my attention to Harriet’s attempts to guide ‘the popular party’ following the 1835 election…

To read part four of Martin’s blog series click here

Further Reading

S. Richardson, ‘A Regular Politician in Breeches: The Life and Work of Harriet Lewin Grote’, in K. Demetrious (ed.), Brill’s Companion to George Grote and the Classical Tradition (2014)

A. Galvin-Elliot, ‘An Artist in the Attic: Women and the House of Commons in the Early-Nineteenth Century‘, Victorian Commons (2018)

Lady Eastlake, Mrs Grote: A Sketch (1880)

J. Hamburger, ‘Grote [née Lewin], Harriet’, Oxf. DNB, www.oxforddnb.com

H. Grote, Collected Papers: In Prose and Verse 1842-1862 (1862)

M. L. Clarke, George Grote: A Biography (1962)

H. Grote (ed.), Posthumous Papers: Comprising Selections from Familiar Correspondence (1874)

Pingback: ‘Restless, turbulent, and bold’: Radical MPs and the opening of the reformed Parliament in 1833 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: ‘She, yes, she was the only member of parliament’: Harriet Grote, radical parliamentary tactics and House of Lords reform, 1835-6 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 – The History of Parliament

Pingback: The ladies’ gallery in the temporary House of Commons | The Victorian Commons