In the fourth of his blogs on Harriet Grote (1792-1878), our research fellow Dr Martin Spychal looks at Harriet’s involvement in the abortive attempt to establish a radical party at Westminster in the wake of the 1835 election.

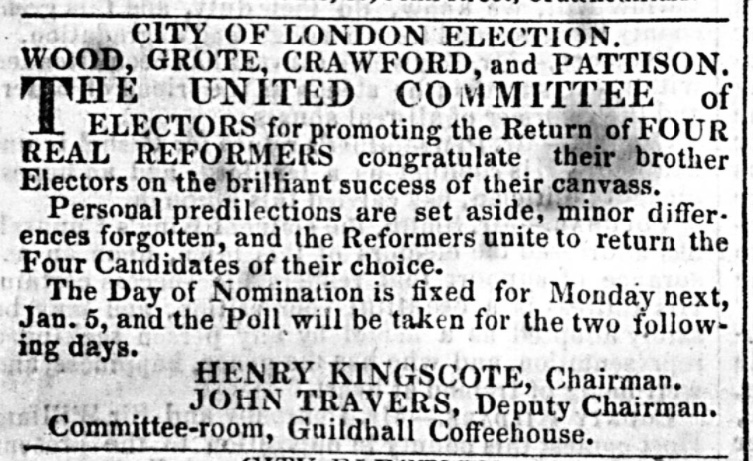

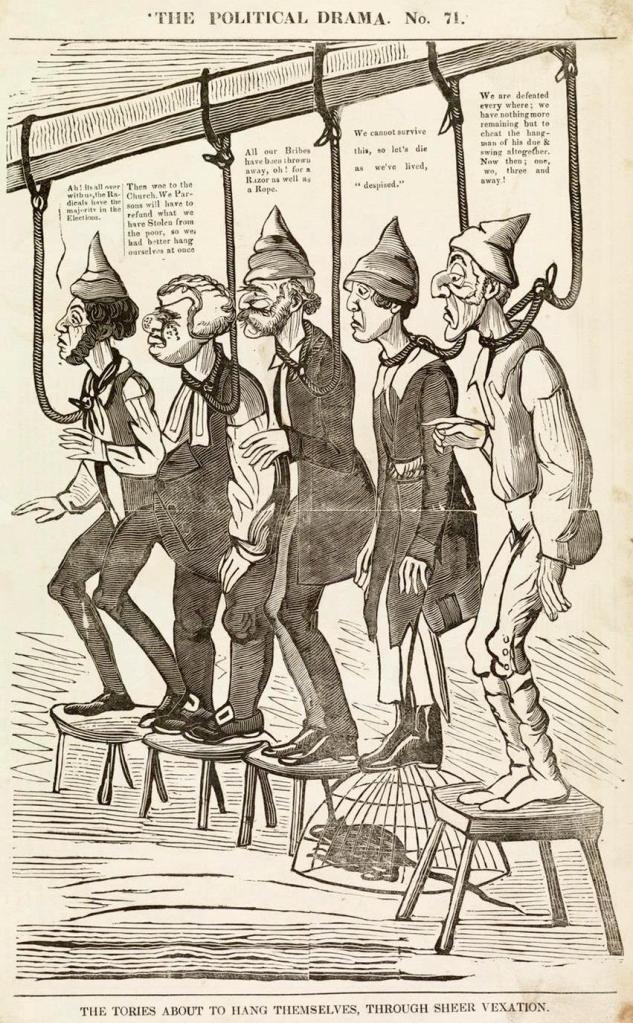

In November 1834 four years of Whig government came to an end with the appointment of a Conservative ministry. The change in government led to a general election in January 1835, which threw Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and her husband, George (1794-1871) into a state of ‘agitation and fervour’. Together, their efforts helped secure George’s re-election, along with that of three fellow reformers for the City of London constituency.

Despite George’s success, at a national level the 1835 election offered worrying signs for those seeking to implement radical change at Westminster. Harriet lamented a lack of new or existing radical political talent, writing in late November 1834 that:

[George] Grote is continually receiving applications from radical constituencies [to stand at the 1835 election], and only grieves that he can’t name a man or two, but he knows none worthy

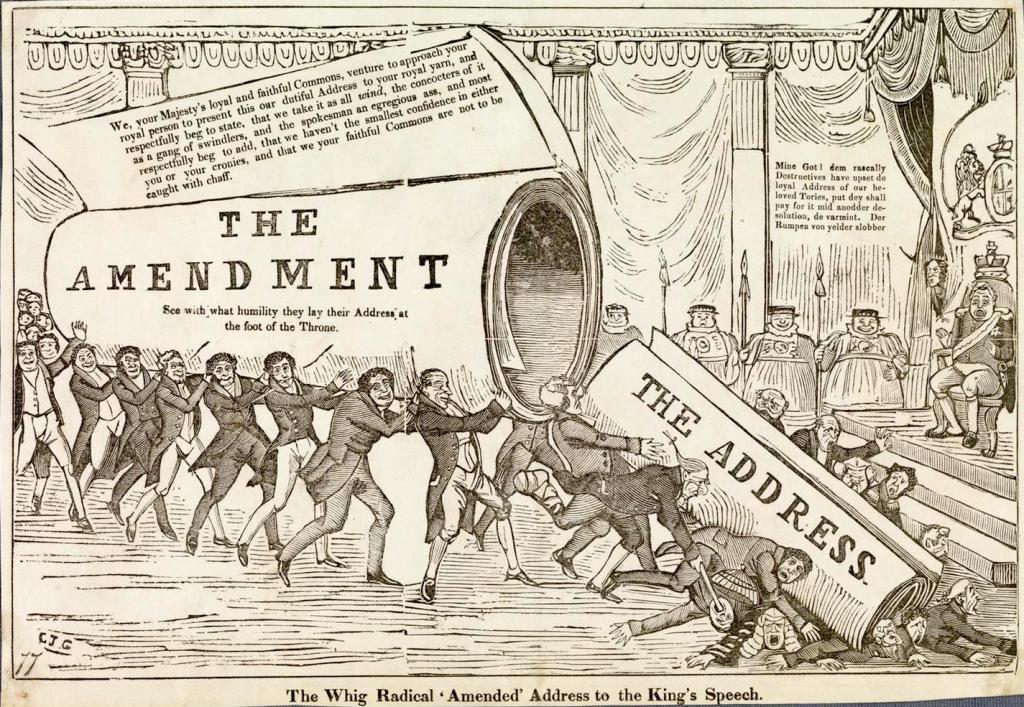

George and Harriet’s scepticism proved somewhat misplaced as the 1835 election actually led to a slight rise in the number of MPs labelling themselves reformers or radicals – from 155 in 1832 to 179 in 1835. This emboldened the Grotes and their allies to try to form a new party of around 70 to 80 trusted ‘independent and pronounced’ radical and reformer MPs, who were to act distinctly from the Whigs and Irish Repealers (the other two opposition groupings to the Conservative government).

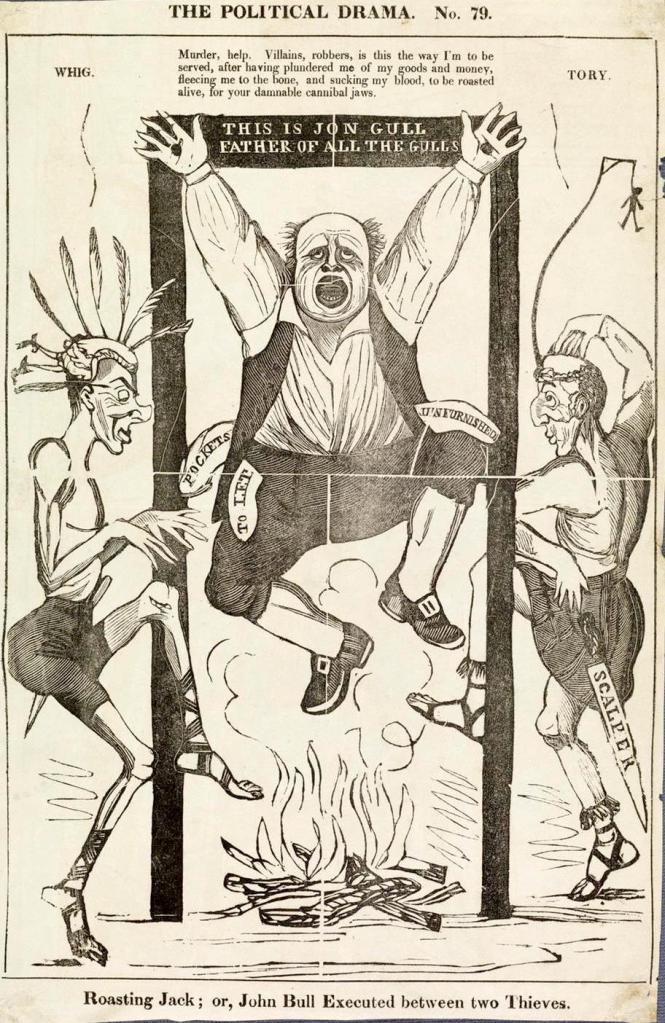

The party’s chief aim, in Harriet’s words, was ‘consultation and combined action among the English radicals’. George, one ally professed, was ‘most probably’ going to act as leader. Their first task was to ensure a coherent radical opposition to Peel’s Conservative government. However, Harriet’s close friend, MP for Cornwall East, William Molesworth, looked even further ahead. He advised his mother privately of his hope that the party would ‘one day or another bring destruction upon both Whigs and Tories’.

Behind the scenes Harriet was one of the central organising forces, losing little time in marketing Grote, perhaps prematurely, as ‘chief of opposition’. She embarked on a letter writing campaign to MPs and their wives and continued to exert her influence as Westminster’s premier radical hostess – both at the Grote’s new ‘handsome and cheerful set of apartments’ at 11 Pall Mall and their weekend residence at Dulwich Wood.

Harriet and George moved to a ‘handsome and cheerful set of apartments’ at 11 Pall Mall for the 1835 session

Harriet’s gender, as well as her unceasing hostility to the Whigs, meant that her involvement proved too much for some. Her most significant enemy in this regard was someone that she still considered a ‘worthy friend’, the election agent and reformer, Joseph Parkes (1796-1865). Ahead of the opening of Parliament, Parkes took it upon himself to act as a middleman between the Whigs and the reformers, supplying intelligence to the Whigs over the Grotes’ plans for a new party.

In January 1835 Parkes alerted the former Whig minister, the 1st Earl Durham, to Harriet’s attempts to disparage another former Whig minister and MP for Manchester, Charles Poulett Thomson. Thomson, who used his Manchester hustings speeches to profess more radical ambitions than some of his Whig colleagues, continued to work with his Whig colleagues, and Parkes, throughout the 1835 election campaign.

To Harriet, Whigs like Thomson who maintained free trade ambitions but refused to support further constitutional reforms such as the ballot or shorter parliaments were not to be trusted. Although surviving documentation is scarce (in general Harriet advised her correspondents to burn her letters), she appears to have started warning reformer and radical MPs against considering alliances with Whigs such as Thomson. Parkes wrote to Durham to warn him of Harriet’s efforts and vent his frustration about her complete aversion to any form of compromise with the Whigs:

I send you another of my female politicians’ epistles ([from] Mrs Grote). Return it to me. I don’t know what in [Charles Poulett] Thompson’s [sic] speech she finds so very seedy. The worst of the radicals is their shadowing refining antipathies.

For historians trying to reconstruct women’s involvement in nineteenth-century politics, Parkes’s suggestion that Harriet was one of several ‘female politicians’ involved in the formation of the radical party is tantalising – and based on her surviving correspondence at the time we might add Sophia Evans (wife of the MP for Dublin, George Evans), and Mary Gaskell (wife of the MP for Wakefield, Daniel Gaskell) to that list.

It is also likely that a desire to keep Harriet away from power motivated Parkes in expressing his opinion against suggestions that George might lead any new party. As we will see in future blogs, this was the beginning of a complete breakdown in Harriet and Parkes’s relationship. For now though, Parkes conceded that although George enjoyed the ‘best status’ among Parliament’s reformers, he was not ideal leadership material. Parkes advised Durham that George, unlike Harriet, lacked the level of cunning to lead a party: ‘he [George] wants Devil’.

Ultimately the new party failed to materialise. The immediate rationale for a radical party faded once it became apparent that Whigs, reformers and Repealers were willing to co-operate to bring down Peel’s Conservative government. However, there was still the question of securing influence over the next government.

The prospects of a new party really ended when the Grotes and their allies became paranoid that a coup had been set in train to establish the leader of the Irish Repealers, Daniel O’Connell, as its head. Many reformers and radicals, including the Grotes, shared a general distrust of O’Connell’s politics and feared he simply sought to prop up a Whig government.

Harriet blamed the machinations of one of her least favourite Whigs, Lord Brougham, and the naivety of the radical MP for Middlesex, Joseph Hume. With word of O’Connell’s involvement circulating around Westminster, potential MPs dropped like flies. In April 1835, Harriet called an end to the episode, conceding ‘our gentleman have next to abandoned the design [for a party]’.

To read part five of Martin’s blog series click here

Further Reading

S. Richardson, ‘A Regular Politician in Breeches: The Life and Work of Harriet Lewin Grote’, in K. Demetrious (ed.), Brill’s Companion to George Grote and the Classical Tradition (2014)

P. Salmon, Electoral Reform At Work: Local Politics and National Parties, 1832-1841 (2002)

J. Hamburger, ‘Grote [née Lewin], Harriet’, Oxf. DNB, www.oxforddnb.com

Lady Eastlake, Mrs Grote: A Sketch (1880)

H. Grote, Collected Papers: In Prose and Verse 1842-1862 (1862)

H. Grote (ed.), Posthumous Papers: Comprising Selections from Familiar Correspondence (1874)

M. L. Clarke, George Grote: A Biography (1962)

Pingback: ‘She, yes, she was the only member of parliament’: Harriet Grote, radical parliamentary tactics and House of Lords reform, 1835-6 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9 – The History of Parliament

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: ‘Another of my female politicians’ epistles’: Harriet Grote (1792-1878), the 1835 Parliament and the failed attempt to establish a radical party – The History of Parliament