Following on from our recent events and blogs marking the 150th anniversary of the introduction of the secret ballot, Dr Philip Salmon explores some of the Act’s lesser known and unintended consequences.

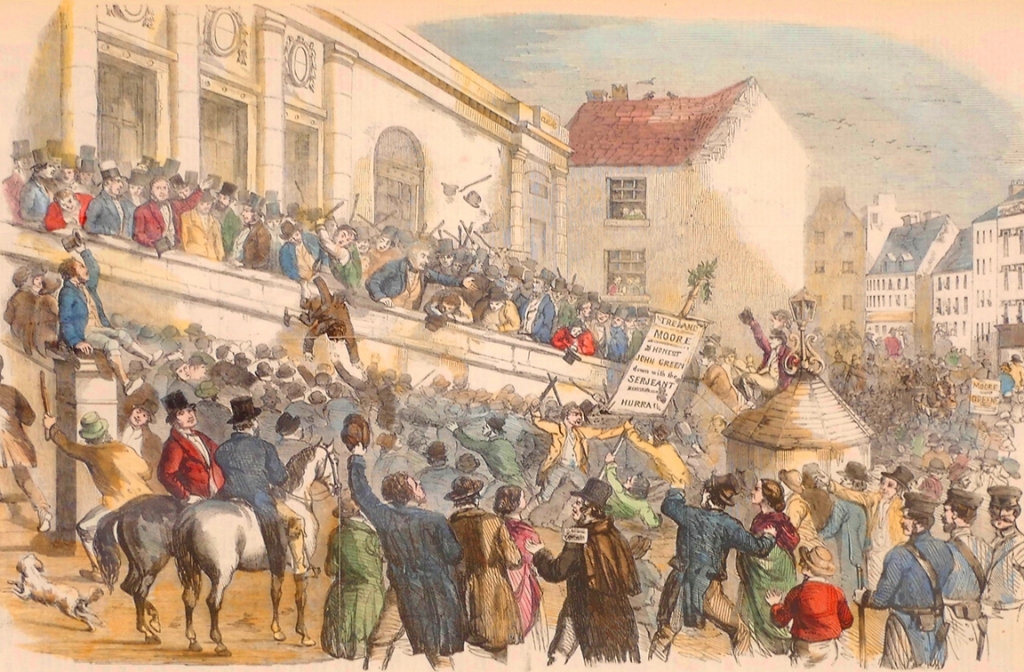

The Ballot Act of 1872 sits alongside the three major Reform Acts of the 19th century (and various Corrupt Practices Acts) in helping to transform British elections into their recognisably modern form. As some of our earlier blogs have shown, it ended a system of open voting and public nominations that had become increasingly associated with bribery, the intimidation of voters and disorderly behaviour, often fuelled by drink.

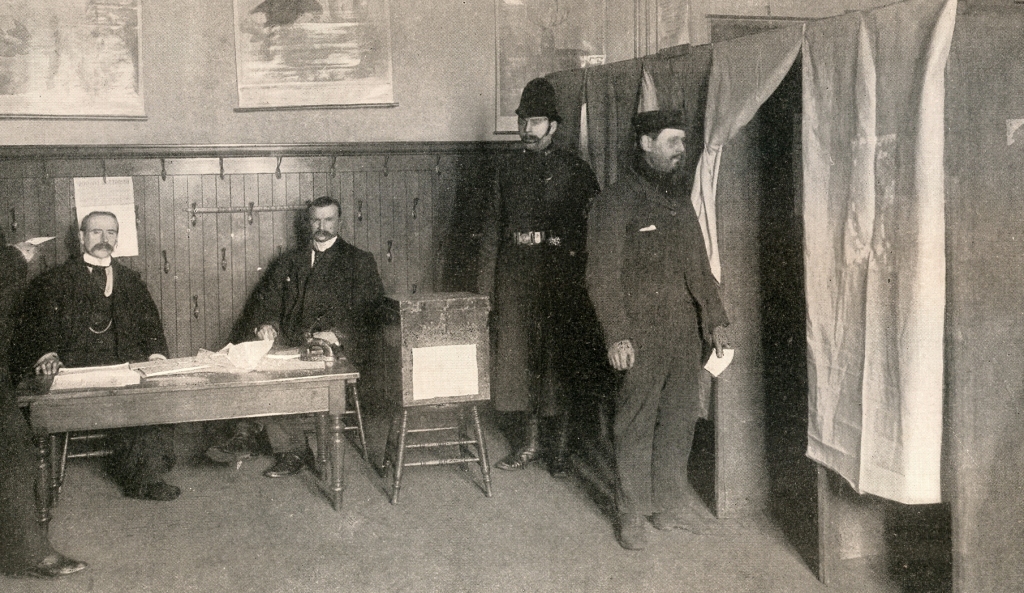

The calmness and order of Britain’s new secret elections, by contrast, was striking. At the first by-elections to be held in Pontefract, Preston, Tiverton and Richmond, it was widely reported that there was none of the usual ‘horse play’ and ‘excitement’. Some commentators even complained that the secret ballot had ‘taken all the life out of elections’, making them ‘dull’. They have become ‘the most monotonous of monotonies’, commented the South Wales Daily News, wistfully recalling the agitation and passion of ‘olden times’.

These and many similar press reports clearly support the idea of a remarkably smooth transition to secret voting, despite some initial hitches in places like Pontefract, which had just 4 weeks to prepare for the new system. However, a number of longer-term issues did begin to emerge in later polls, which have received less attention. At the municipal level, in particular, problems began to occur in places where multiple councillors were being chosen in each ward. Reports of electors inadvertently crossing the wrong combinations of boxes, because the official ballot papers listed the candidates differently to the leaflets they had received, or of electors being confused about how many crosses they could use, or even writing their names on the ballot as they had done previously in municipal elections, began to fill the local newspapers.

Illiterate voters appear to have had a particularly difficult time. Great fun, in a typically cruel Victorian fashion, was made out of one ‘gaily attired’ female voter at Sheffield’s first council elections held using the secret ballot, who after declaring ‘in the loudest of tones’ that she ‘could not read’, had to be physically restrained by the returning officer from shouting out her votes. She was promptly taken aside and ‘amidst the laughter of those in the room’ made to whisper her choices, before being given a lecture about ‘learning to read’.

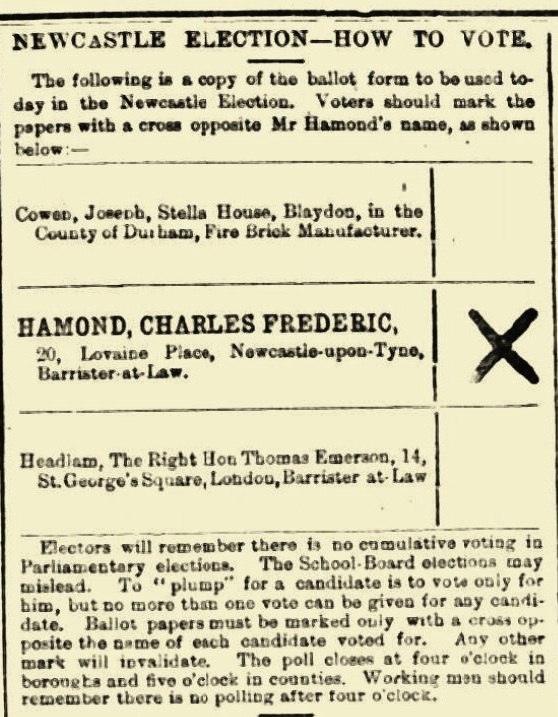

The biggest problem, however, which was to become a significant issue in the 1874 general election, was the question of how to cast a good old fashioned ‘plumper’ in those constituencies that continued to elect two (or more) MPs. It is often forgotten that unlike today with our first-past-the-post system, before 1885 the vast bulk of England’s parliamentary seats were multi-member. This created a much more complex voting system in which electors could either divide their support between different candidates or use just one of their multiple votes to support a single candidate, by casting a ‘plumper’. Shortly before the 1874 general election the Reading Mercury, 31 Jan. 1874, published this extraordinary but by no means uncommon advice:

If the voter intends to vote … all he has to do is put a cross (X) against the names of the candidates … Of course if the voter intends to give a “plumper” two crosses must be written opposite the name of the candidate thus favoured.

Reports soon filled the press of voters up and down the country either intending to or actually casting multiple votes for one candidate, all of which, as agents and their candidates frantically tried to point out, invalidated their ballot papers. Many newspapers, especially the London-based journals, blamed this confusion about plumping on the cumulative voting introduced alongside the secret ballot for London’s School Board elections in 1870. Under this system voters could, and often did, cast multiple votes for a single candidate.

The plumping problem, however, was not just confined to London’s constituencies. In Brighton one horrified Conservative candidate reported receiving multiple letters of support from voters saying ‘I shall give my two votes for you’. Fearing the worst, on the eve of the poll he issued a special address, warning that ‘if my voters shall commit that error, hundreds, if not thousands of votes would be lost’. In Sunderland one draper, questioned by a candidate, ‘said he meant to give him his two votes’. Things got so bad in Glasgow that special notices had to be issued telling electors that ‘you cannot give more than one vote to any one candidate or mark more than one X after the name of such candidate’.

Plumping was just one of the traditional forms of voting in multi-member seats that clearly did not translate smoothly on to the modern ballot paper. Unaided by the public conversations with clerks and agents that used to take place before electors orally declared their votes at the poll, many electors also struggled with selecting the appropriate combinations of candidates, especially in the absence of party labels on the ballot papers.

One upshot of all this, with long-term consequences, was the stimulus given to local party organisations in the constituencies to produce better guidance and campaign literature and develop new types of electioneering. Aided by their efforts, a deluge of additional information and advice about how best to support either the local Conservative party or the Liberals soon became available. But where did this leave the non-party voters, the backbone of the old public voting system, whose votes it must be remembered accounted for around one-fifth of all those cast between 1832 and 1868?

The data currently available indicates that non-party voting – either supporting candidates from different parties (in what amounted to a cross-party vote) or casting a non-partisan plump (voting for only one candidate from a particular party even when others were standing) – declined significantly in the 1874 and 1880 elections, for the first time dropping below 8%. The move to secrecy, it seems, made the whole business of casting non-party votes in multiple member constituencies more complex and liable to confusion, requiring a greater political awareness and level of knowledge on the part of the voter.

It would not be long of course before this whole system of multiple votes and being able to make non-party choices would be almost completely eradicated, making the use of the new secret ballot papers much more straightforward. After just one more general election in 1880, and yet another dramatic expansion of the franchise in 1884, most of the UK shifted to winner-takes-all single member seats in 1885 – a system that for better or worse, continues to define our modern party politics today.

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Politics beyond party: the survival of non-partisan traditions, 1832-68 | The Victorian Commons