It’s been a long time since the business of suspending Parliament and starting a new session has generated so much political controversy. Throughout most of the 20th century prorogations invariably tallied with the expectations of most parliamentarians, neatly book-ending a government’s legislative programme. Scroll back a little further into the 19th century, however, and a rather different picture emerges …

Parliament’s historic procedures and conventions have generated a huge amount of public interest recently. Responding to popular demand, the latest version of Erskine May’s Parliamentary Practice, detailing the ‘law, privileges, proceedings and usage of Parliament’, has even been uploaded online. What readers won’t find in the latest edition, however, is much information about prorogation. Beyond stating that it is a personal prerogative power exercised by the Crown on the advice of the prime minister, which ends the current session of Parliament, there is remarkably little discussion of how and when prorogation can or indeed has been used, particularly for political purposes.

Before becoming so routine and un-contentious in the 20th century, however, prorogations were often attracted a fair amount of controversy. Occasionally they even aroused popular indignation and triggered public protests, such as the one organised in Manchester in September 1841 against the new Tory government’s decision to prorogue during an economic crisis and sidestep calls for an inquiry into the corn laws. Petitions and memorials from across the country had flooded into Parliament urging MPs to remain in session and alleviate the nation’s starvation and distress. On 7 October 1841, however, the new prime minister Sir Robert Peel prorogued Parliament for almost four months.

A number of factors helped to make prorogation decisions more open to question in this period, including the looser nature of the two-party system, the existence of many more minority governments, and the much greater power of the House of Lords, which was far from being the subservient chamber it is sometimes assumed to have been.

What really made prorogations stand out and potentially so controversial, however, was their length. Today we are used to prorogations lasting days – the recent average is eight. Over the past 40 years no prorogation has lasted more than three weeks.

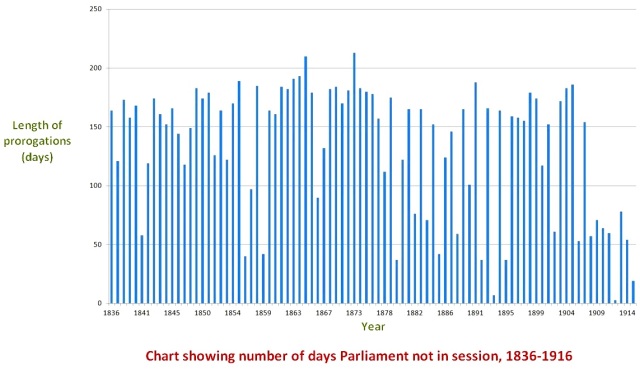

During the 19th century, by contrast, they usually dragged on for months, sometimes for almost five and on occasion even six months. The graph above plots the length of the breaks between each session of Parliament from 1836 to 1916. As such it also includes prorogations that were followed by a dissolution and a general election – a more drawn out process in the Victorian era than it is today. In 1873, for example, Parliament was prorogued on 5 August. On 26 January 1874, a few days before it was scheduled to reconvene, it was dissolved on the advice of the Liberal prime minster William Gladstone. A general election then took place and Parliament did not sit again until 5 March 1874, making a total break of 213 days (around seven months) during which Parliament was not sitting.

Even removing all the prorogations that were followed by dissolutions, however, still leaves an average prorogation length that seems extraordinary by modern standards. The mean duration from 1836-1916 was 142 days, over four and a half months. In practice this meant that for much of the Victorian period, Parliament was prorogued and not in session for over a third of any given year.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Victorian prorogations, however, and the one that maybe has the most contemporary resonance, was the correlation that often existed between their length and some sort of national crisis or major political upheaval. Put simply, when things got tough, governments tried to avoid Parliament as much as possible.

In 1838, for instance, the Whig ministry of Lord Melbourne was accused of deliberately proroguing Parliament for too long, for 173 days, in order to avoid discussion of their incompetent handling of rebellions in Canada and Ireland and their decision to go to war in Afghanistan. ‘Ministers are afraid to meet Parliament … they are afraid to encounter Parliamentary scrutiny’, protested the Tory press.

Lord Aberdeen’s government also had no intention of allowing its disastrous handling of the Crimean War to be exposed to any more parliamentary scrutiny than was absolutely necessary. When one of their own supporters tried to move for an address to the Queen against prorogation, in July 1854, they made it a matter of confidence, forcing its withdrawal.

Many of the minority governments of the 19th century made ample use of prorogation, for obvious reasons. The Conservative leader Lord Derby, keen to avoid a repeat of his short-lived first minority ministry of 1852, kept his second minority government of 1858 going for far longer than expected with the help of a six month prorogation – one of the longest on record. His successor as Conservative prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, also managed to keep the lid on a major political row within his own party and between the Commons and the House of Lords over church reform by proroguing Parliament for a similar period in 1874.

The use of such tactics inevitably meant that public campaigns and petitions for and against prorogation were a much more familiar occurrence than we are used to. The scale of the famous prorogation protests of 1820, however, was unusual. In November Lord Liverpool’s Tory government had been forced to abandon its hugely unpopular attempt to prosecute Queen Caroline for adultery, much to the fury of her estranged husband George IV. Rather than risk an inquiry, which the opposition were demanding, the prime minister prorogued Parliament, prompting nationwide demonstrations. At one rally in Durham, the Tories were accused of acting ‘unconstitutionally’ in order to ‘terminate discussion and popular protest arising from their persecution of Queen Caroline’ and ‘silence the indignation they had aroused’.

It has been a long while since the issue of prorogation triggered these sorts of levels of political commentary and public activism. Given recent events, the next edition of Erskine May may well have to provide a few more details about the use of this ancient procedure than it does now.

Further reading:

P. Salmon, ‘Exploring the History of Prorogation’, Times Literary Supplement, 6 Sept. 2019

Pingback: Prorogation and Adjournment – Reformation to Referendum: Writing a New History of Parliament

Reblogged this on The History of Parliament.

Pingback: On the History of Prorogation – History Workshop

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: The royal scandal that helped change British politics: the 1820 Queen Caroline affair – The History of Parliament