Our research fellow Dr. Martin Spychal shares some insights from his work on the BBC Radio 4 series, Prime Ministers’ Props…

I’ve recently been working with our former editorial board member, Professor Sir David Cannadine on the second series of his BBC Radio 4 series Prime Ministers’ Props. Each episode examines how a Prime Minister became associated with a certain object or prop in the popular mind, and how that prop came to define the public image of the premier in question. After a twentieth-century focused first series, this time around three of our five episodes focus on nineteenth-century prime ministers: the Duke of Wellington, Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone.

One of the major means of understanding the public image of these three men is via the satirical cartoons, and early photographs, that accompanied their political careers. Wellington’s political rise and fall at Westminster between 1827 and 1830 was book-ended by two prints that mocked his connection to his famous prop – the Wellington boot.

The Wellington boot had been designed for Wellington and his troops during the Napoleonic Wars, and in post-war Britain became the footwear of choice for the fashionable gentleman. In October 1827 William Heath depicted Wellington, replete with huge cocked hat, appearing out of a Wellington boot. Wellington had recently been re-appointed as commander-in-chief of the British army under Viscount Goderich’s short-lived administration. As well as satirising the fact that Wellington was now at the head and the foot of the army, the smugness of the Duke’s face adverted to the pressing likelihood of his appointment as Prime Minister. Wellington had recently cemented his position as leader of the Protestant right of the Tory party after defeating William Huskisson’s 1827 corn law bill in the Lords, and while Goderich’s political position grew weaker during the autumn of 1827, Wellington embarked on a speaking tour of the north of England where he was feted by his supporters as a leader in waiting.

Sure enough, in January 1828 Wellington was appointed Prime Minister. It was not a happy premiership, however. During his first year in office he lost standing with his supporters on the ultra right over his government’s 1828 corn law, and test and corporation legislation, and several key liberal-Tories resigned from his cabinet over parliamentary reform. Catholic emancipation in 1829 saw him lose even more friends on the right, and by the general election of 1830, many of the Tories who had lauded him in 1827 were, along with the radical press, outwardly accusing him of supporting the recently toppled Bourbon monarchy in France and seeking a military dictatorship via the newly formed Metropolitan Police. The final straw for Wellington came in November 1830 when he controversially declared that Britain’s notorious system of rotten boroughs ‘possessed the full and entire confidence of the country’, which helped spark riots in London. Wellington was forced to resign with his political authority in tatters. In response, William Heath likened the Duke and his home secretary, Robert Peel, to an unwanted ‘pair of left off Vellingtons to be sold wery cheap’.

Disraeli and his novels are the subject of our second episode. Throughout his career they provided ammunition for satirists and commentators seeking to decode his political ambitions. Disraeli’s first novel, Vivian Grey (1826), which charted the political travails of Vivian Grey and his ruthless pursuit of power, proved easy pickings. When Disraeli first became Prime Minister in 1868, the satirical magazine Fun couldn’t help joking that ‘Vivian Grey’ had been ‘Sent For’.

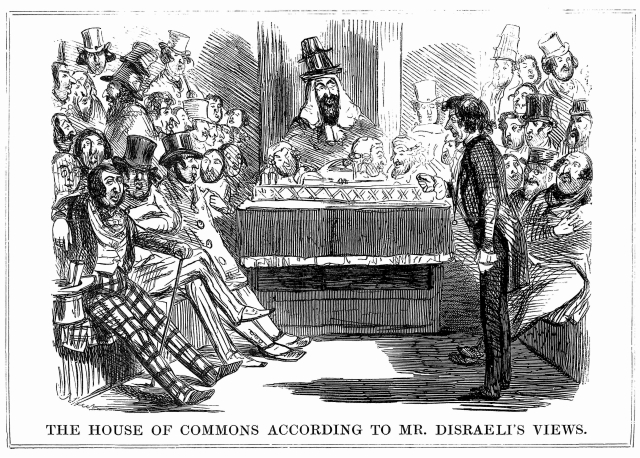

However, contemporaries dug much deeper than this for hidden meaning in his novels. One example of this is an early Punch cartoon, which followed Disraeli’s 1847 novel Tancred. It offers a disconcerting taste of the anti-Semitic criticism that Disraeli, a practising Anglican of Jewish descent, faced throughout his career.

As with several of his books, Tancred centres on a protagonist and his quest for moral and religious fulfilment. For his critics, the characters in these novels offered proof of Disraeli’s ‘eastern’ bias and his desire to infect the British constitution with these alleged views. An article that accompanied the cartoon mocked Disraeli as the ‘Jewish Champion’, and warned that Tancred offered confirmation of his desire to turn the House of Commons into a ‘Mosaic parliament, sitting in Rag Fair’, a reference to the market in Houndsditch, London, popular with Jewish traders. The cartoon itself is equally disturbing, depicting Britain’s leading politicians in stereotypical Jewish clothing, with their faces imagined in anti-Semitic caricature.

Disraeli’s great rival, the Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone, provides the focus of our third episode. Gladstone’s prop was his axe. A committed axeman since the 1850s, Gladstone actively played on his love of tree-felling to portray himself as Britain’s premier political woodsman, committed to chopping down the roots of corruption in the British constitution. As well as in cartoons and speeches, Gladstone expertly manipulated the new technology of photography to perpetuate an image of him in his leisure time at his Hawarden estate, felling trees as a plain-clothed, masculine labourer.

From the later 1870s cabinet cards and carte-de-visites of Gladstone with his axe at his Hawarden estate adorned the mantelpieces of Liberal supporters, and Gladstone’s cultivation of his woodsman image was so successful that his axe-head became the official emblem of the Liberal party during the 1885 general election.

In 1886, however, Gladstone’s axe received perhaps the most bizarre pictorial treatment, when one ‘C. B. Harness’ claimed that his cure-all ‘electropathic battery belt’ was responsible for Gladstone’s continued vitality. As well as providing perhaps the only example of a Prime Minister advertising a toning belt, the unauthorised use of Gladstone’s image in adverts such as this, along with the widespread success of Wellington boots and Disraeli’s novels, are an important reminder of the centrality of politics to nineteenth-century culture.

You can catch the remaining episodes of this series on BBC Radio 4 at 9:30am Wednesdays. All episodes will be available through BBC iPlayer after their initial broadcast.

Further reading:

- M. Dent. ‘“There Must Be Design”: The Threat of Unbelief in Disraeli’s Lothair’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 44 (2016), 671–686

- D. Hamer, ‘Gladstone: The Making of a Political Myth’, Victorian Studies, 22 (1978), 29-50

- S. Mayer, ‘Portraits of the Artist as Politician, the Politician as Artist: Commemorating the Disraeli Phenomenon’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 21 (2016), 281-300

- H. Miller, Politics Personified: Portraiture, caricature and visual culture in Britain, c. 1830-80 (2015)

- R. Muir, Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace 1814–1852 (2015)

- P. Sewter, ‘Gladstone as Woodsman’ in R. Quinault, E. Swift & R. Clayton Windscheffel (eds.), William Gladstone : new studies and perspectives (2012)

- A. Wohl, ‘“Dizzi-Ben-Dizzi”: Disraeli as Alien’, Journal of British Studies, 34 (1995), 375- 411

Reblogged this on The History of Parliament.

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons for 2019 | The Victorian Commons