Victorian politics was frequently conceived and constructed around horse and racecourse related allusions and analogies. Given the ubiquity of the horse to 19th century life this is hardly surprising. A tantalising insight into this genre appeared 30 years ago in James Vernon’s pioneering Politics and the People (1993). But on the whole modern scholars have paid remarkably little attention to the way equine inspired political concepts helped to shape public perceptions of politicians and parties, and how developments within these terms of reference reflected broader shifts at work in a rapidly industrialising and urbanising society, in which the role of the horse itself began to undergo fundamental change.

At almost every level of politics – from the fate of bills and parties in Parliament, to the use of ‘whips’ to control MPs, to elections with candidates ‘going the course’ under competing ‘colours’ – equestrian terms and imagery were used to conceptualise political activity and events. Obvious legacies of this appropriation of horse related vocabulary include the term ‘first past the post’ to describe the electoral system in single member constituencies.

Reinforcing this equine-centred political culture, politicians themselves were often as fond of ‘the Turf’as they were of Parliament, with many leading figures hosting and patronising world-class racing fixtures, including most famously the Tory leader and prime minister Lord Derby. Lord George Bentinck, the leader of the agriculturalists who opposed Peel’s commercial free trade policies in 1846, splitting the Tory party, was just one of many highly influential MPs obsessed by the Turf. For Peel’s more vehement opponents it seemed entirely fitting (and perhaps no coincidence) that after repealing the protectionist corn laws and ‘betraying’ England’s agricultural interest, Peel met an untimely end after being thrown and crushed by an unruly ‘hunter’ horse, having ignored the warnings of his groom.

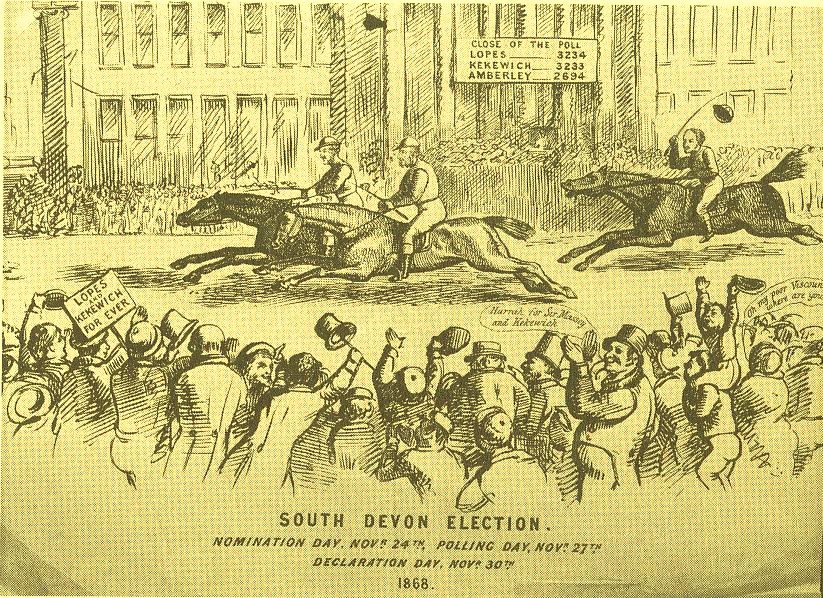

At election time, the horse came into its own. This was not just because of the endless racing terms and analogies used in election contests but also because the ‘conveyance’ of voters and related horse-hire formed a substantial chunk of most candidates’ election expenses. Marching horses and horse drawn carriage processions were also an integral part of the public theatre and ritual of Victorian electioneering.

Once in Parliament the associations continued. The calendar itself – the timing of adjournments, recesses and sessions – was designed to facilitate attendance at the great equestrian events of each season, as one of our previous blogs about Derby Day has shown. In debates, the role of the horse and associated appliances served as a standard metaphor in discussions about almost every conceivable subject, often shaping the conceptual framework around which a policy or initiative was interpreted and argued.

When the Liberal party famously split apart over the 1866 reform bill, for example, one of the main objections was that the bill separated enfranchisement from redistribution, ‘putting the cart before the horse’ as many rebel Whig-Liberal ‘Adullamite’ MPs complained. But as one of the bill’s more radical supporters explained, ‘it was necessary to know the size of the cart and the weight to be carried before the proper number of horses to draw it could be determined on’.

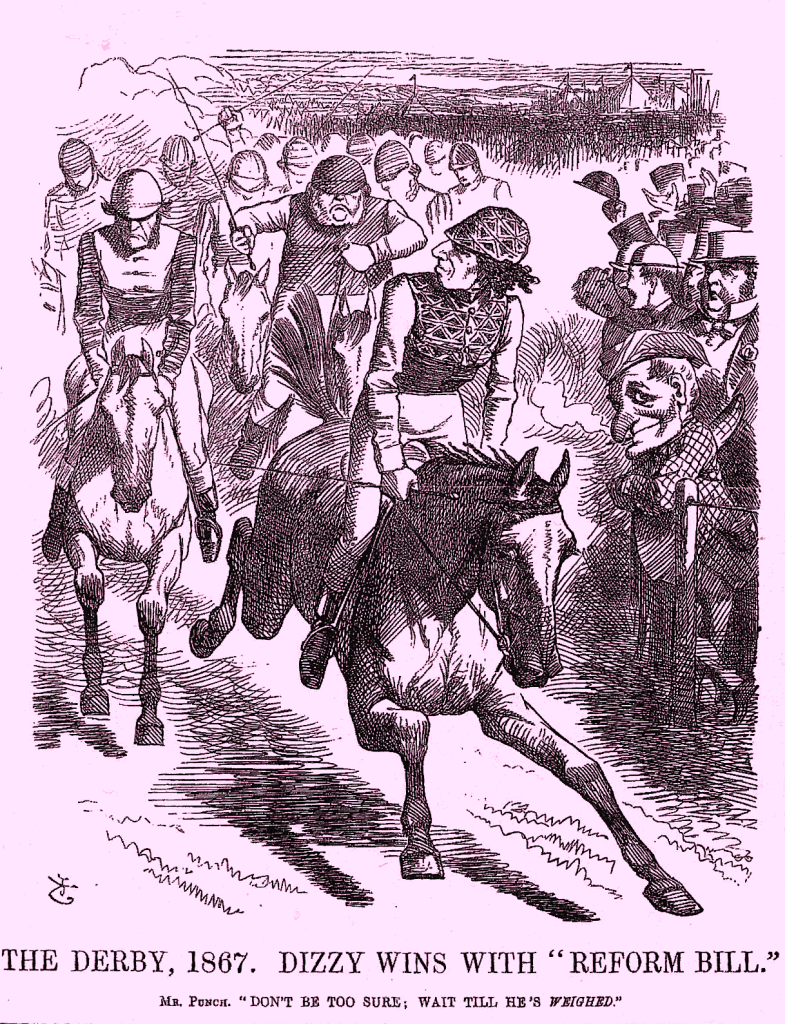

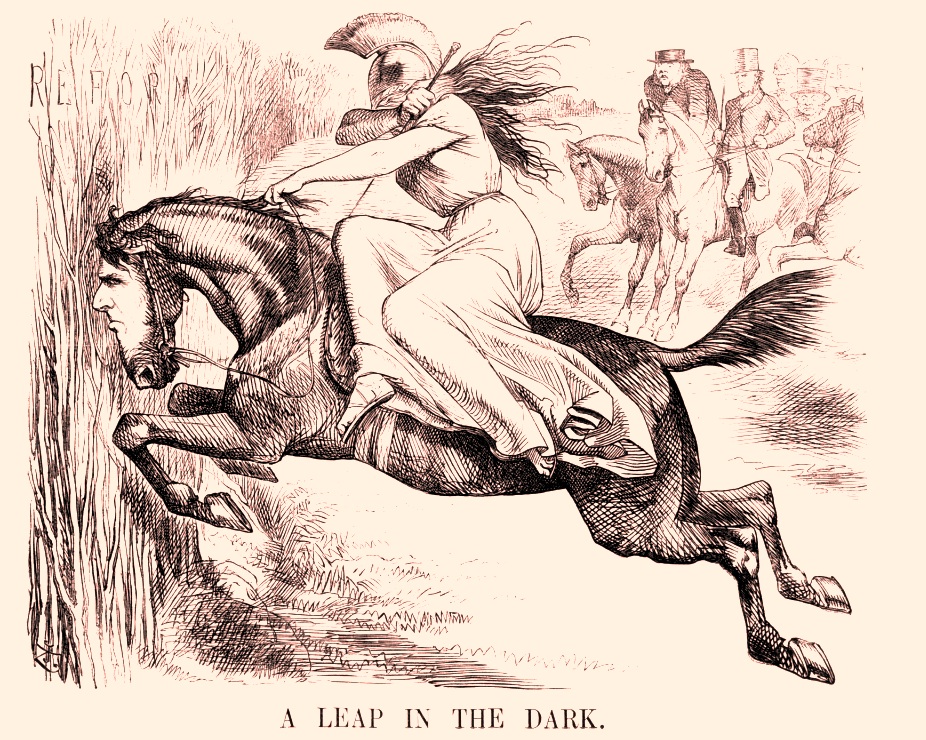

Fittingly, when the Tory government passed its seismic 1867 Reform Act the following year, against all ‘odds’, the bill was almost universally caricatured as a horse, either winning a race against the Liberals or breaking loose and taking a mammoth ‘leap in the dark’ with the UK constitution.

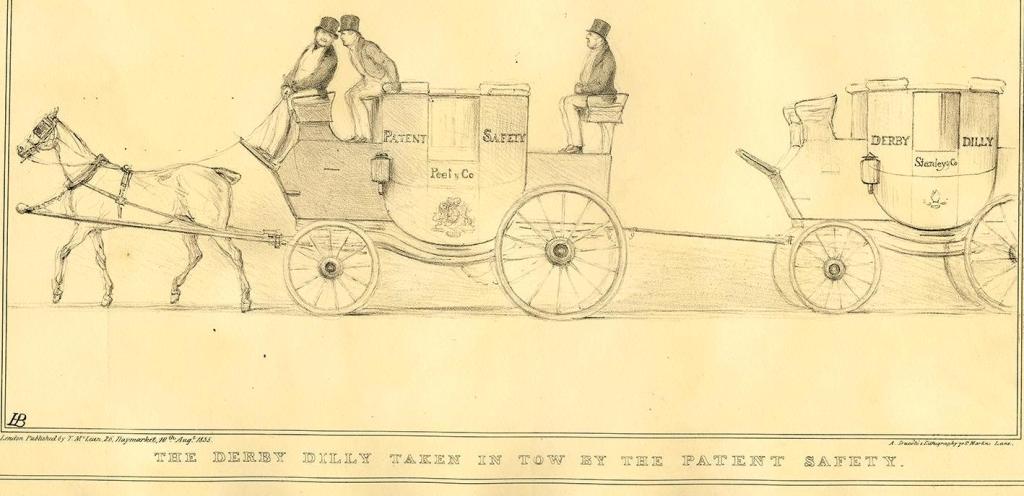

The allusion here to the earlier 1832 Reform Act, also widely caricatured as a horse or a horse drawn coach in texts and imagery, would have been clear to contemporaries. In one particularly popular image, for example, a ‘reform’ horse carrying a terrified monarch was portrayed vaulting both ‘vested interests’ and a ‘revolutionary torrent’, while being chased by a pack of Tory wolves.

Decoding these sometimes rather obscure (to a modern observer) references adds a new layer of understanding to the way early Victorian politics was framed, discussed and perceived by many contemporaries, especially at the more popular level. The central role of equestrian metaphors and imagery, in particular, serves as a reminder of just how important the horse was, not only in everyday Victorian life but also for the construction of an entire political mindset.

Related info: click here for the programme of a recent conference on ‘The Horse and the Country House: Art, Politics and Mobility’

Pingback: Happy New Year from the Victorian Commons! | The Victorian Commons