For most modern commentators the prospects for minority governments, based on the experience of the last half century or so, don’t look particularly good. Nearly all the recent examples currently being revisited by analysts, such as those of the 1970s, have been short-lived and devoid of any major legislative achievements. Go back another century, however, and a rather different picture emerges. During the 19th century, when the UK’s parliamentary system was still evolving and party loyalties were less rigid, minority governments were not only more common but also provided opportunities for important political realignments and even some major constitutional reforms.

Sir Robert Peel’s Tory ministry of 1834-5 was the first to set the agenda for the operation of minority governments in the new era of popular politics that followed the ‘Great’ Reform Act. Formed less than two years after the landslide victory for the Whigs at the 1832 election, which left the Tories with less than 150 MPs, Peel’s ministry owed its existence to the interference of the King, who controversially dismissed the Whigs over their proposals to reform the Irish church and installed a Tory government instead. Peel’s insistence on calling an election – in which he produced his famous ‘Tamworth manifesto’ – and his attempt to adapt his policies to attract disaffected MPs in other parties created an important precedent, in which MPs were morally encouraged to support policies rather than parties, and back ‘measures not men’.

Extract from original Tamworth Manifesto, 1834

Although Peel lost the 1835 election, securing some 291 firm supporters to the Whig-Liberals’ 322, the existence of about 45 undecided MPs, many of whom backed Lord Stanley, a former Whig trying to form his own third party, left everything to play for. Peel lost major Commons votes on the address (i.e. on the King’s speech) and the appointment of a new speaker, and even suffered a humiliating rebellion within his own ranks over the taxes imposed on malt production. However, he did not resign until he was defeated in April 1835 on the Irish church, the issue which had brought him to power. Far from being a lame duck ministry, during the 140 days that this minority government held power it managed to introduce a number of key initiatives, most notably on reforming the outdated finances of the Church of England, but also on other controversial issues like church tithes and civil marriages.

Another Conservative prime minister oversaw not just one but three minority governments. The career of the Earl of Derby, as Lord Stanley became in 1851, provides another example of how Victorian prime ministers were able to govern and even implement major reforms without enjoying a Commons majority. This former Whig turned Protectionist Tory led ministries in 1852, 1858-9 and 1866-68. Like Peel, he encouraged a ‘measures not men’ approach to parliamentary behaviour, although he left his leader in the Commons, Benjamin Disraeli, to sort out what this meant in practice. He also fought elections, in 1852 and 1859, in an unsuccessful bid to secure a majority, but like Peel only felt obliged to resign as prime minister after a Commons defeat on a central issue. His legislative achievements included finishing off two highly controversial measures which had been initiated by the Liberals. One completely changed the way India was governed, abolishing the long-entrenched monopoly of the East India Company, and the other, despite being a thorny issue with Protestant Tory hard-liners, allowed Jews to sit in Parliament.

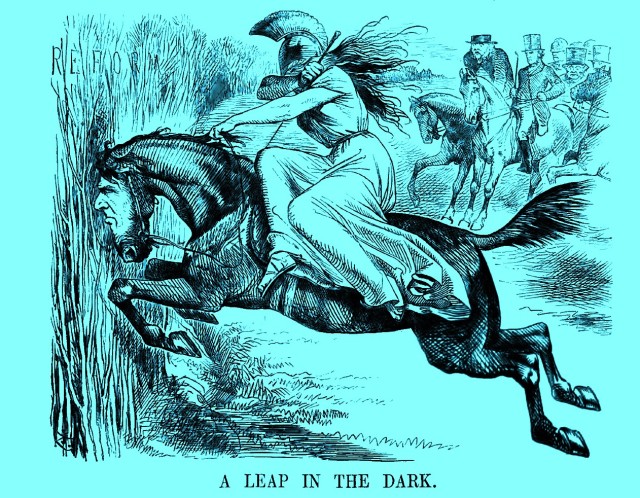

This ability to absorb and adapt policies that would be difficult for other parties to oppose was perhaps nowhere more evident than in the parliamentary shenanigans surrounding one of the most far-reaching measures of the mid-Victorian era: the so-called ‘leap in the dark’ 1867 Reform Act. It seems extraordinary that this major constitutional reform, dramatically extending the vote to a large proportion of working-class men and almost doubling the electorate, should have been passed by the Tories, the party that had done the most to prevent the far less radical ‘Great’ Reform Act of 1832. It is even more astonishing that this second instalment of reform, long lobbied for by radicals and Chartists, should have been passed by a Tory minority government some 70 MPs short of their rivals.

Disraeli (the horse) taking Britannia into the unknown, 1867

The story of how the Liberals’ reform bill of 1866 split the Liberal party into warring camps, allowing Derby and Disraeli to seize power and implement a free-for-all approach to policy-making that resulted in the 1867 Reform Act, provides one of the most revealing episodes in ‘parliamentary government’ on record. By accommodating almost every demand that secured majority Commons support, and skilfully exploiting the hopes and fears of his dubious party supporters in both Houses, Disraeli, in particular, turned minority governance into an art form.

Future blogs celebrating the 150th anniversary of the 1867 Reform Act, later this year, will explore the passage and impact of this major achievement in more detail. Whether minority governments in our own era can pull off a similar feat remains to be seen.

Pingback: Lord Derby, ‘centre’ parties and minority government | The Victorian Commons

Pingback: Sir Robert Peel and the modern Conservative party | The Victorian Commons