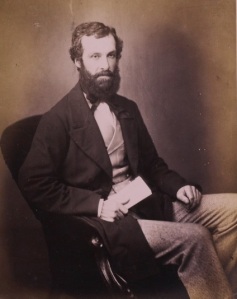

One of the most striking features of researching Victorian MPs is the extraordinary range of abilities and interests they often possessed beyond the Commons chamber. Previous blogs have highlighted well known figures like William Henry Fox Talbot, the inventor of photography, and Sir George Cayley, the pioneer of flight, to name just a few. But there were also many other multi-talented individuals who, for one reason or another, have not received much historical attention. One such man was William Coningham (1815-84), Liberal MP for the fashionable seaside resort of Brighton from 1857 until 1864.

Described by George Eliot in 1851 as ‘a disciple (not yet run mad) of Robert Owen’s’, Coningham was both a leading figure in the Victorian art world and an unlikely early English socialist. Born into a wealthy family with military connections, he briefly attended Trinity College, Cambridge, where he mixed with the so-called Cambridge Apostles, before embarking on an army career. Finding barrack-yard society uncongenial, however, he soon bought himself out. Thereafter he toured the Continent and fell under the spell of his influential cousin John Sterling, the celebrated author and associate of Thomas Carlyle. He also began to research and buy Italian Old Masters, often in Rome for a ‘small price’. By 1847, aged just 32, he had assembled one of the finest art collections in Victorian England, mostly ‘on his own initiative, without advice from dealers or other connoisseurs’. Many of these paintings, such as his ‘little Giotto’ of the Pentecost in the National Gallery, now hang in major museums.

In 1847 Coningham agreed to stand as a second Liberal candidate at Brighton, where he lived with his wife, two children and a dozen servants. Although defeated, he remained politically active. In 1851, in a significant but much neglected publication, he called for the establishment of working men’s co-operative associations as a means of adjusting ‘the proportional division of profits between capital, labour, and talent’. Distancing himself from communism, where equality was enforced, and ‘vague’ socialism, he suggested that profits from co-operatives should be allocated in proportion to ‘investment and input’, citing the example of the pianoforte co-operatives in Paris. Adopting a more strident tone at a meeting of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers the following year, he defended the railway engineers’ ‘right to combine’ against their ‘tyrannical employers’, adding that ‘the working classes not only paid an enormous proportion of the taxes of this country, but they had to suffer from the monopolies of the aristocracy’. That month he also presided at meetings of the striking railway engineers on the London, Brighton and South Coast railway.

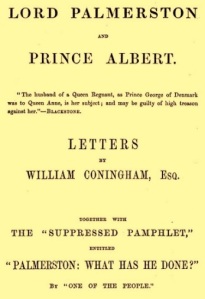

When Coningham stood unsuccessfully as a ‘people’s candidate’ for Westminster in 1852, he was branded ‘a Communist, an Anarchist, and a Republican’ by his opponents. His eventual election for Brighton in 1857 was based on his outspoken support for Palmerston and his foreign policy, which included a pamphlet outlining a conspiracy theory involving senior ministers. Convinced that Palmerston had long been the victim of ‘unconstitutional’ plotting by Prince Albert and the Coburg family, he accused the royal family of pursuing their own ‘Teutonic’ ends, perverting both the political and cultural life of the nation.

When Coningham stood unsuccessfully as a ‘people’s candidate’ for Westminster in 1852, he was branded ‘a Communist, an Anarchist, and a Republican’ by his opponents. His eventual election for Brighton in 1857 was based on his outspoken support for Palmerston and his foreign policy, which included a pamphlet outlining a conspiracy theory involving senior ministers. Convinced that Palmerston had long been the victim of ‘unconstitutional’ plotting by Prince Albert and the Coburg family, he accused the royal family of pursuing their own ‘Teutonic’ ends, perverting both the political and cultural life of the nation.

These themes were to feature prominently in many of his increasingly fiery speeches in the Commons. In 1857, for instance, he recommended ending the grant to the Princess Royal, as she was about to marry a German and would therefore ‘become identified in interest with a foreign house and a foreign dynasty’. A related bugbear was the way the Royal Academy and National Gallery pandered to the ‘teutonic element’ in their methods of art restoration, as introduced from Berlin by Gustavus Waagen. Coningham’s vitriolic attacks on Waagen, whom he accused of ‘gross incompetence’, accepting ‘forgeries’ and ‘numberless intrigues’, were described by The Times as ‘contemptible slander’. Coningham’s real venom, however, was reserved for the ‘barbarous’ and ‘Germanic’ Gothic style being adopted by the Commission of Fine Arts for London’s public buildings, including the ‘bastard Gothic’ House of Commons.

Increasingly frustrated with the Palmerston ministry’s inactivity over political reform, Coningham also began to warn that they would be ‘called to account’ and ‘repent of what they were doing’, earning him reprimands from the Speaker. By the early 1860s his spats with ministers and other Liberal MPs were becoming legendary. Reporting one incident in the summer of 1863, his fellow MP Sir John Trelawny noted:

The sun gets hotter, and debates follow suit. Coningham and Osborne have been fighting … O. interrupted C. on a supposed point of order. C. doubted whether O. was sober. O. doubted whether C. was sane … The two combatants damaged themselves and the House.

On another occasion Trelawny observed how, ‘Coningham spoke, lashing himself into a fury. He begins quietly. Gradually, the House interrupts. Then he gets off his balance, and for a time seems almost insane’.

By 1863 it was indeed likely that Coningham was suffering from some form of mental illness, as his wife’s unhappy correspondence seems to indicate. He resigned his seat in 1864, citing ill health, only to attempt an ill-advised return to politics by running against the leading Liberal Henry Fawcett at Brighton in 1868. This backfired disastrously, leaving him bottom of the poll and ostracised by his former allies, among them John Stuart Mill, who alluded to Coningham having been corrupted or ‘gone native’ as an MP. Coningham’s remaining years were spent mainly abroad, in steady decline.

For details of how to access the full biography of William Coningham and other Victorian MPs click here.

Further reading:

W. Coningham, The Self-Organised Co-Operative Associations in Paris and the French Republic (1851)

F. Haskell, ‘William Coningham and his collection of old masters’, Burlington Magazine (1991), cxxxiii. 676-81